|

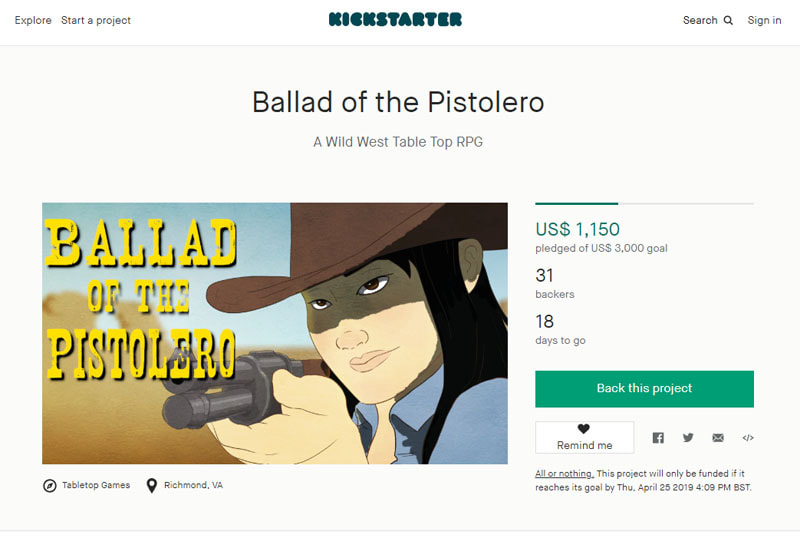

My favorite roleplaying system to run is Legend of the Five Rings (L5R): a fantasy samurai setting where characters find themselves fighting just as hard in the political ring as the martial fields. I find myself naturally drawn to systems where the pen is at least as mighty as the sword. Because of this, I was naturally drawn to L5R’s social combat: intrigue scenes. So I quickly was drawn to Fantasy Flights newest edition of the game. Characters in L5R have to rely heavily on their social skills as well as combat prowess in these scenes where progress toward predetermined political or social goals is tracked mechanically, similar to progress in a combat encounter. This is the feature that drew me to L5R, but I recently realized that in my year and a half of GMing it, I have almost never used the social system, and now I have to know why. Is this an inherent flaw in the idea of a mechanically-heavy social encounter? A flaw in the specific rules L5R uses? Or my failure as a GM? 1) What’s The Point? In any roleplaying system, by the time combat begins, the players already know their objective; the question the players are answering is how not what. Typically the heroes will win; it is simply a matter of how much damage they will take, what price they will pay, and how they accomplish their goal. This allows combat to give player choice in a way that structures without hindering the GM’s ability to let the world respond to them. Social combat should ask the same questions. The purpose of social combat is not to seek an end result but rather to ask questions about a known end. Who will the players owe a favor to? How many different weaknesses of their enemy did they uncover? How many of their own weaknesses did they reveal in the process? Starting a social scene by trying to determine the player’s next course of action is like rolling initiative before knowing if there is even a monster in the room. L5R even pushes players towards this end by having players decide beforehand what their goal in the scene is. Both social and martial combat aims to answer how and if players are successful, not what players are successful in doing. 2) Breaking Plot Armor Asking the incorrect questions in social combat leads this to become a tool to take control of characters out of the GM’s hand. The main reason why physical combat is so mechanical is that the GM doesn’t govern the physics of the world, just people in it. In many social situations, player success is determined by the people in the world, not the world itself and it’s mechanics. NPC’s can choose to be unreasonable but they can’t always choose not to be on fire. The more interesting parts of roleplaying are watching players decide what kind of deals to make and what kind of solutions to take. Any social combat should support this goal while still leaving its questions open ended. Social combat needs to be more than rolling to see how a character reacts to something said to them. Players should be asked to problem solve not simply to construct what they are saying. 3) Social Battlefields Of course, the tools that we can use in our systems are only as good as the setting that we put them in. One game that does this well is another one of my favorite roleplaying games, Urban Shadows. The heavy focus on political factions, not individuals, is what makes this stand out to me as opposed to the L5R intrigue system. Urban Shadows continually focuses on the setting as the true main character of the story. The landscape of a game of Urban Shadows sets a political battleground that presents players with multiple options. Social combat often wants to track how successful you are at convincing a political leader to assist you without accounting for options to go around them like working with that political leader’s enemies. Players need to be given the space to choose which characters they want to work with. L5R’s equivalent “battlefield” needs to present the players with more options than the standard “what do you say to the one person I told you to talk to”. This is why these systems work better when the subject matter involves vying for political control. L5R’s intrigue system has a scope that is a bit too small. Focusing on individuals rather than groups and individuals’ roles within those groups. L5R and several systems have the capability of this but don’t give the necessary backdrop often enough to support it. Focusing on this bigger picture gives the players more options to attack a problem without being overly restrictive with rules. More codified social conflict rules can give a game system a lot of strength, however I feel like they can be really hard to use. It’s harder to set a stage where talking your way out is actually the correct answer. However, a lot of my most memorable sessions don’t revolve around a large combat encounter. Rather, they are centered on my players coming up with unique manipulations of the characters in the story. A lot of the community inherently associates story heavy systems with rules light systems. This leaves ideas for mechanically heavy story-driven games unexplored. I believe that the correct implementation of this kind of system could make a really unique and interesting system that we are currently missing out on. Bo Quel is a Legend of the Five Rings Fanatic From Virginia. He plays and GMs several systems where he focuses on telling enriching stories and making characters that are memorable. He also is the GM/Host of Secondhand Strife, an L5R RPG actual Play Podcast. Picture provided by the writer. Whenever I’ve brought up RPGs from Japan to people, their minds go to the most obvious sort of imagery: ninja, samurai, those neat looking castles, and maybe Shaolin monks (whom are more closely related to the Chinese). After all, most games in the western market are Fantasy based on Medieval Europe, it’s not too much of a stretch to think Japan would do the same. That isn’t exactly true, since a quick look through the Japanese Amazon site’s 本 (book) section for the term “TRPG” actually yields Call of Cthulhu as their first result, as well as (at least as of this writing, Summer of 2019) the Konosuba and Goblin Slayer TRPGs. The Japanese roleplayers seem to at least harbor a similar love for feudal Europe as we do, though mystery and horror are also big hits there. However, with the way Amazon’s algorithms work, only the most popular things at the time will typically float to the top, and so if you want to find something really unusual, you should expect to do some digging and asking around. As it turns out, Tenra Bansho Zero isn’t the only game that provokes ye olde Nippon imagery out there the Japanese have made. Today, for your reading pleasure, I will tell you about Shinobigami, one of Japan’s RPGs about a modern day ninja war! 1) Who Made This? Shinobigami was originally published in Japan by Roll and Role Imprint, with the English version being translated by Kotodami Heavy Industries, the same company that brought us Ryuutama and Tenra Bansho Zero. KotoHI announced Shinobigami and successfully funded the publishing effort via Kickstarter in 2015. The translation effort for Shinobigami took a great deal of time, for much the same reason that Tenra did: there are numerous cultural nuances that the translation team wanted to preserve. An additional obstacle KotoHI had to overcome was some of the updates to the technology surrounding crowdfunding games such as Backerkit, and the incompatibilities these new tools have with Japanese banks. These constant delays lead to fans of KotoHI starting a call and response in joke whenever somebody would mention Shinobigami. One group would shout “WHEN” and another would reply “SOON.” 2) What’s The Premise? Shinobigami is a game about the very sort of thing one might expect when they hear the phrase “Japanese roleplaying game”: it’s a game set in the modern day about ninjas, fighting an invisible war against one another. Though it’s not enough that they’re ninjas in a world of secrets and espionage; the ninjas in Shinobigami are superhuman! They all move at superhuman speeds and perform feats that are otherwise not humanly possible as if those feats were nothing. Plus, every ninja belongs to one of many different clans with their own agendas and traits that make them unique, such as a clan dedicated to serving Japan’s national interest, or another that’s composed entirely of supernatural beings such as vampires and werewolves. Basically, Shinobigami is a game set in the modern world with all manner of intense ninja action! 3) What Are It’s Mechanics Like? The game follows a pattern of players taking turns choosing between Drama Scenes and Combat Scenes with other characters. Their objective is to discover what each other’s secrets are, as well as setting themselves up to accomplish their mission. After so many cycles, all players take part in a grand battle known as the Climax Phase where everybody involved in the scenario fights each other. During this battle, you either team up with those you think you can trust, or against everybody else. What truly makes Shinobigami unique is the Skill Matrix: a table of 60 some odd skills that you have no chance of mastering all of since you’ll typically only have 6. However, anytime a particular roll is called for and you don’t have that skill, you can substitute another skill in place of it at a slight penalty based on how far apart the two skills are on the matrix. Assuming you can explain why that substitution should be allowed, that is. This can lead to bizarre or even hilarious circumstances, such as explaining how Necromancy can be counteracted with Cooking. 4) What’s It Similar To? In practice, Shinobigami is a game of hidden information: you’re learning secrets and other information, and trying to deduce what the best course of action is based on what you can find out. This makes it much akin to games like “Werewolf” or “Mafia.” Though for the unfortunate players that lack guile, there’s a few added steps between the mob deciding to kill your character and then dying. Shinobigami uses a game engine known as Saikoro Fiction, best explained as one of Japan’s narrative focused games. The skill matrix is a recurring part of other Sai-Fi titles, such as Beginning Idol and Yankee vs Yog Sothoth. The other hallmark of these games is that the rules are built around supporting a narrative, e.g. any skill can be used in place of any other, as long as you explain why, and are willing to take the appropriate penalty. (These penalties don’t include the absurdity of your explanation, only how far apart they are on the matrix.) 5) Is It Worth Getting Into? Yes!! Kotodama Heavy Industries has brought two other games to the English speaking world, and has done them great justice in the translation. This attention to detail made the wait for each of them worthwhile. Shinobigami is therefore a great example of what RPGs from Japan look like, a fact that the translators took great pains with Shinobigami to ensure. The first half of its rulebook is what the Japanese call a Replay, similar to Actual Plays, but on a written medium instead. The second half of the book contains all the rules needed to play. Shinobigami also demonstrates that gamism and narrativism can be a false dichotomy. It has rules that are specific and must be followed, yet don’t interfere with building narrative. (In fact, sometimes it promotes narrative!) Shinobigami is in my list of games that everybody should play at least once. Aaron der Schaedel sat on this article for half a year, waiting for the release of Shinobigami to be finalized before he passed it along to the editors. This is still a shorter time than he and many others waited for the release of Shinobigami. Apropos of nothing, here’s a link to his Youtube Channel. Picture Reference: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/diamondsutra/shinobigami-modern-ninja-battle-tabletop-rpg-from Barak thumbed the edge of his axe as he listened to his companion drone on about the intrigues of court. Prince Kheldar was a master of political schemes, but Barak would have none of it. Give him a good honest fight any day. “Get to the point!” he snarled. “Did you talk to your aunt about the Bear Cult?” Kheldar nodded. “You aren’t going to like it.” “She won’t help?!” Barak was incredulous. “Oh no, she’s fine with it. We can get the information we need...if we all come to dinner tonight.” One of the ancestors of the D&D game is the writings of H. Rider Haggard, whose barbarian protagonists solved problems in Gordian fashion. There can be a refreshing clarity to quick violence, but domains like Richemulot, Borca, and Dementlieu are expected to have courtly intrigues, and Nova Vaasa and Darkon are no strangers to social schemes. If you’re looking for a challenge that doesn’t look like a battlefield, consider a formal social event. Whether a private dinner party or a public auction, a social event can have all the thrill of slaying a dragon, if you focus on these seven major challenges. For the first six, it’s easy enough to assign points for varying degrees of success and total them up at the end. The seventh requires a little more scorekeeping, but it’s all worth it to hear a player yell that their insult landed a critical hit. 1) Pleased To Meet You It’s normal for adventurers to brag about their exploits, but few cultures view brave deeds as the first thing they want to know about you, and many consider it gauche for you to tell the tales yourself. You’ll need to know if formal introductions are based on noble titles, academic degrees, lineage, birth sign, or something else. If you rank below your peers on this yardstick, it’s usually best to admit so up front with a little modesty and wait for an opportunity to speak about your deeds. A good host may give you an opportunity to do so immediately, or a respected member of the group might step in when you are forced to be modest. 2) A Token Of Esteem Depending upon the occasion, formal gift giving may be expected. If not, it pays to know how a small unexpected token would be received. Whether you’re giving, receiving, or exchanging, gifts represent status, and the subtext underneath a particular choice may have many layers. In the real world, a single birthday gift of Cuban cigars, for example, might snub other gift-givers by the price tag, beard the authorities by being contraband, and bear a secret reminder of a lost weekend in Cuba. On other occasions, gifts can scream rather than whisper. A powerful figure who knows her rival intends to publicly shame her with a priceless gift at their next meeting may hire outsiders to steal it, or to find something worthy of exchange. 3) Clothes Make The Man In all but the most barbaric of societies, social gatherings call for clean clothes, but that’s just the beginning. Clothes indicate status as much as gifts, and following the latest trends in fashion--or deliberately setting your own--involves a significant amount of time and attention. Even the smallest accessories can speak volumes, and usually do: social movements often identify themselves by a pin, badge, or ribbon showing you support the cause. Even without such explicit accessories, adept socialites can convey subtle messages in the choice of a hat or lapel pin. Reading the messages in a person’s clothing may grant a bonus towards influencing them, or at least eliminate the faux pas of asking where someone stands on a matter when they are literally wearing their sympathies on their sleeve. 4) Soup Or Salad? You can generally judge how challenging a dinner party is going to be by the number of courses. Each course has a specific set of expected behaviors: utensils to use, bites to take, how to speak, etc. To know how to behave, a PC can either rely on their knowledge of nobility, or just watch other people carefully and do what they do. Prepping ahead of time can grant a bonus to either of these rolls. Failure, however, means an error that the character must mitigate diplomatically to avoid diminishing their status in the eyes of those present. 5) Small Talk: The Smaller The Better Career adventurers will get the reputation of being crass and insensitive unless they learn to avoid “shop talk” around people who don’t engage in regular mortal combat. The weather may be a boring topic, but it’s a safe one: it’s slightly different every day and no one can be blamed for it. Topics with equally high variety and low sensitivity might include crop expectations, the latest opera or public games, and how fast children grow. Middling territory for small talk would be things like popular books and what people do for a living. If someone at the table brings up politics or religion, that doesn’t make it open season. You’ll usually score more points by steering the conversation back into safe waters than you will by joining in on boorish behavior. 6) Double Your Speak, Double Your Fun It’s rude to have prolonged side conversations at the table, so folks who want to go beyond small talk had better get good at hidden meanings. Know your default values to exchange innuendo, and consider establishing code words and phrases ahead of time to grant a bonus to these checks. The Message spell is also useful for unobtrusive speech, but the whispers it employs can be overheard. Try covering your mouth with a napkin, or whisper while pretending to take a sip of wine. Once away from the dinner table you may be able to talk more freely with your target, but only if you have an excuse to meet together. Even the most casual meetings can become fodder for gossip, especially across political lines or between sexes, especially in societies that have strict gender roles. 7) Casual Debate Small talk is intended to avoid arguments, but some settings actually call for something more spirited. To engage in a casual debate is perhaps the closest thing to social combat, and I highly recommend the use of some kind of reputation point system so players can actually feel the progress of the fight. For example, you can extrapolate the “hit points” and AC of each person’s argument from their related skills and abilities, and let people take aim at an argument using various social skills in place of an attack roll. Everyone should have a role to play, but those roles are often reversed from traditional combat: if a previous support character like a bard is suddenly the front-line fighter, allow the mighty thewed barbarian with minimal social graces to support the bard by laughing at jokes and glaring at the opponent to throw him off. Done properly, a good social event can feel like the party went through a minefield blindfolded, followed by a pitched battle. The fact that reputations were the only casualties only complicates the matter, because losers may have long memories and yearn to settle the score. Of course, this is an adventure game, but you should have enough here to keep it from being boring even before things take a turn for the deadly. If your players enjoy it, you can discuss whether they want just the occasional change of pace or a longer detour. Who knows? Your next campaign might be set in a more socially dangerous setting. With scheming courtiers hiding behind pleasant faces, there’s hardly a need for monsters at all. Leyshon Campbell has been playing and writing for Ravenloft for over twenty years, from the Kargatane's Book of S series, playtesting D&D 3E in a Ravenloft campaign, to the ill-fated Masque of the Jade Horror. He married his wife on Friday the 13th after proposing to her on Halloween. By tradition, the first story read at birth to each of their three children was The Barker’s Tour, from Ravenloft’s “Carnival” supplement. He is currently running the “Queen of Orphans” Ravenloft campaign. Picture Reference: https://www.etsy.com/listing/688840794/monte-cristo-invitation-regency-wedding As a dude with a history degree, one of my pet peeves is people taking pop history and the way history has been presented through media at face value. Vikings didn’t wear badass leather biker outfits like you see on TV. Spartans had armor and didn’t fight with their abs bared for all to see. And not all cowboys were white dudes. That peeve is one that seems to be shared by Chris Spivey of Darker Hue Studios. Chris recently launched a Kickstarter for his new game Haunted West, a weird west setting with a focus on bringing to life Western stories we don’t typically hear about, weird or otherwise, and sat down to answer a few questions. Where does the history of Haunted West diverge from our own? As the Kickstarter has officially launched, I can say that it happens a few years into the Reconstruction and immediately after the Civil War. Haunted West: Reconstruction creates a timeline in which, in addition to taking out Lincoln, Booth's plot also eliminates Johnson, who is from the South and a former owner of enslaved people, as he had originally intended. Lafayette Foster becomes President, and without presidential opposition, the Southern confederates are not allowed back in congress. The land is divided and given to the enslaved people as was actually planned in our known history, changing the power dynamic of America, with black landowners battling against traitors who are terrorizing them and trying to steal their legally-owned land. We are creating an ongoing narrative of how that one moment changes the world as we know it. What sets Haunted West apart from other Weird West settings like Deadlands and Wild Wild West? That is kind of like asking what sets Star Wars apart from Star Trek or DC Heroes from Marvel Super Heroes. The games are different in approach, setting, tone, and have different teams behind them. Haunted West is doing something no other current Western RPG has done, to my knowledge. We are telling the true history of America while highlighting many of the people whose voices have been forgotten, providing an entirely new and unexplored timeline, and including a three-tiered modular system. That's just the tip of the iceberg. You’ve developed a new system for Haunted West. Is it based on an established system, or is it something we’ve never seen before? The Ouroboros System is unique in its approach to modular play and has a number of easy-to-apply rules. The core mechanic is a 1D100 roll under system with degrees of success and failure that have different impacts. Skilled Paragons are able to invest a portion of their successes into ‘The River’ and use that portion for a later challenge when the chips are down. Each skill is associated with 1 of 7 different attributes that confer a starting percentage in the skill. You’re best known for your work in the Cthulhu Mythos, and at first glance, it doesn’t have much in common with Haunted West. What led you to work on a Weird West setting? The Mythos and I (trademarked!) may be the first musical I write in a few years. One of the stretch goals is actually to introduce the Mythos into the Weird West. I am hoping we hit that one. Part of the reason I chose the Weird West was my love of Westerns that came from watching them with my grandmother every Saturday morning growing up. Watching those paragons of the west making the world better became our ritual. But it always bothered me that no one looked like me unless they were cast as the villain or, sometimes, the butt of the joke. Haunted West aims to change that. It lets me add my knowledge and interest in the supernatural, history, science fiction, and cinema. The Weird West is such a large and expansive genre encapsulating so many different things--the skies the limit. What kind of tools will you have in place for developing frontier towns and settlements? I am known for my love of random chart generations, ranging from scenarios to encounters. You can fully expect charts, directions on how a town should be built, and the tools a Narrator (how we refer to Game Moderator in Haunted West) will need. With your work for Call of Cthulhu, Cthulhu Confidential, Chaosium’s new sci-fi game that you’re heading up, you’re a pretty busy guy. How much support do you plan to have for Haunted West post-launch, and what plans do you have in store for Darker Hue Studios moving forward? That’s a great question. I actually have quite a bit of time and fully intend to use it for Darker Hue Studios. I am finishing up Masks of the Mythos, The Mythos in Scion, for Onyx Path and have turned in my work for City of Mist by Son of Oak, Doctor Who for Cubicle 7, and my superhero book to Chaosium months ago. At the moment, Chaosium, with the recent acquisition of a few new game lines (Pendragon and 7th Sea), has put the science fiction game on hold. Pelgrane Press has my last Langston Wright adventure for Cthulhu Confidential, and now I have something that I have not had in years: time. So, I can fully support Haunted West and maybe even turn my hand to writing a novel. I have this burning idea for a science fiction piece and now I have the time to do it. “Don't mistake my kindness for weakness. I am kind to everyone, but when someone is unkind to me, weak is not what you are going to remember about me.” - Al Capone Check out Haunted West on Kickstarter here. Phil Pepin is a grimdark-loving, beater extraordinaire. You can send him new heavy metal tunes, kayak carnage videos and grimdark RPGs on Twitter: @philippepin. What is 'Pulp'? Pulp is a series of sub genres usually set between and around the world wars. It was named after the very cheap material it was produced on, wood pulp. The result was a cheap book ideal for a time of financial depression in the states. Almost everyone bought pulp novels to take their minds on amazing adventures with daring heroes and dastardly villains. These stories were over the top and cut to the good stuff of the stories. Some famous authors had their break writing pulp fiction, including HP Lovecraft, L. Ron Hubbard, and Robert E Howard with his Conan series. So what makes a pulp story good? How can we implement this into a game? Well hopefully I can help with that by giving you some tips for running a pulp RPG setting. 1) Characters Should Be Larger Than Life Characters are the centre role for your story, from the players to the villains. In pulp that means they have the most drama around them: when they show up things go down, hoodlums slink off to inform their boss of your arrival, who just so happens to be sitting in a darkened corner of the speakeasy,and then bullets fly as a grand shootout ensues. 2) Throw In A Timer Any time that a scene is lacking in tension, add a timer, things like a bomb timer is on the nose and fits well. “But what if explosives aren't in my game?” I hear you ask. Well, anything that forces the players to act fast is a timer. A collapsing building, the villain escaping, someone bleeding out; these are all great examples of natural timers that add a sense of urgency. 3) Grand Dialogue You've no doubt seen the movies where the Big Bad and the hero have witty back and forth every time they meet. Those scenes are pulpy as hell. The cheesy one liners delivered after a fight and the villainous monologue explaining key details of a dastardly plan… all pulp. Don't be shy to encourage this with your players, as they will enjoy a break in seriousness and you will collectively gain some great anecdotes to share with fondness. 4) Out Of The Box Thinking Reward any player who comes up with an idea that is so crazy it might just work. Creating a catapult using a plank of wood a small stack of wooden pallets and another player jumping is worth a little GM help to pull off, these ideas help reinforce tip 1 that the characters are larger than life and have the potential to do insane and incredible things. 5) Don't Take It Too Seriously Pulp was brought about to help the working class through the depression after World War One so it was designed originally as light hearted adventure stories, so people could escape the poverty of daily life. Later it evolved into some more serious aspects, but the feeling of pulp is best explored with a slight tongue in cheek approach. 6) Be Inspired There is a plethora of pulp sources in the world, from the original stories printed on the cheapest paper available to glossy movies from the 80s like Indiana Jones or Star Wars. Even in modern day films you can still see the influence of pulp ideas, of over the top heroes having fantastic adventures. Great examples include any film based on a comic or those which have a child chosen by destiny or other unseen forces to fulfill a role by defeating a darkness. Pulp influences are everywhere. We see them everyday without even noticing it. Pulp is all about heroes battling evil and doing so in style. They leap from a moving train and gracefully land in the saddle of their horse, who somehow can run faster than a train at full speed. They swing from a vine through a forest that somehow doesn't seem to descend lower than the hero needs it to and lasts as long as is needed. Pulp villains deliver monologues, they twirl their evil mustaches, and they are almost equally larger than life as the heroes. They reappear after you think they have died; they escape just in time. However you run your pulp game… enjoy it! Ross Reid is an enthusiast, currently running a Achtung! Cthulhu campaign, while studying nursing, he has contributed several articles to HLG and is a strong advocate for all things FATE. Picture Reference: https://paizo.com/products/btpy8oj2?Rolemaster-Third-Edition-RPG-Pulp-Adventures A while ago, I talked about Shadowrun: Anarchy, a rules-light version of Shadowrun that uses a narrativist ruleset called “The Cue System.” I’m not normally a fan of narrativist games. My experience is usually that most of the game elements I like get stripped out in favor of giving more wiggle room to keep the narrative in place. As I was digging around, I discovered that Catalyst Games Lab applied the same rules system used in Shadowrun: Anarchy as they did the Valiant Universe RPG. Having recently got my hands on a copy of the Valiant Universe RPG, and being a casual (but uninformed) fan of Valiant Comics, I spent the next few hours reading it and sharing details about it to my friends who also like Valiant. So today, for your reading pleasure, I present to you: 5 Reasons The Valiant Universe RPG is Super! (Hint: Most of them come down to “The Cue System Is Great For Narrativist Games.”) 1) Title Exposés Any comic multiverse, mainstream or indie, is going to have a large collection of characters, settings, worlds, and story arcs: such is the nature of any medium that’s constantly being written, with an ever increasing lore. The Valiant Universe is no exception. The Valiant Universe RPG uses Title Exposés, two page long series of synopses, to bring potential players and gamemasters up to speed on the setting. As many modern games seem wont to do, every Exposé is led by various tags and cues for what that arc is about. For example, if you were looking for something involving advanced technology, you can take a quick look at Shadowman’s Tags (which includes terms like magic, necromancy, and spirits) to see if it’s worth reading further. 2) Organizations and Sample Characters The Title Exposés use a lot of Proper Nouns, without much further explanation. This is normally a pet peeve of mine, especially in original fiction. However, the Valiant Universe RPG functions a little bit more like an encyclopedia: even when something is mentioned in one place, you can often find another detail about it elsewhere. This is where Organizations and Sample Characters come in. Many of the named characters or organizations are further described, and in the case of characters, they likely have a stat block for them. Just like the Exposés, they include tags and cues, too, so you there’s no wrong place to start; be it organizations, characters, or arcs. The most important thing about the organization section, however, is that it describes not only their involvement in the setting, but also their day-to-day activities, meaning there’s plenty of room in the Valiant Universe for original characters! 3) Scenario Briefs There’s sample characters, organizations, and different settings abound explained for people new to the Valiant Universe, but what if, even with all that, a potential GM still has trouble fitting all this information together? Enter the Scenario briefs! These, like the Title Exposés, are two pages long and list cues and tags for players to work with. They follow the familiar Three Act Structure, with a setup, confrontation, and resolution across the introduction and three scenes. Furthermore, it lists objectives for the player characters to follow, and even refers to sample NPCs that might appear in given scenes! 4) The Cue System One of the most prominent features of the Cue System is what the system gets its name from: Character Cues. These are one-liners and taglines that describe characters, settings, and scenarios. Some of the setting cues don’t mean as much if you’re not already familiar with the setting. However, if you notice a character you like in character section, you can make a note of their tags and flip through all setting, character, and scenario sections that share that tag to get a better idea of how everything fits together. 5) Valiant Comics Setting A few years ago (when I could still afford them) I was a big fan of comic books. While I usually followed Marvel, I also really liked indie or smaller press companies, such as Malibu, Image, and even Valiant. Ever since I was a young boy, I always gravitated towards strange and unusual things, favoring Robert Frost’s proverbial Road Not Taken. It’s often led to me finding some real gems, and in modern days, things that address people’s grievances with pop culture. Valiant is one such case. While many, including yours truly, sometimes bemoan how DC and Marvel comics reuse the same plots while rebooting their stories ad infinitum to create an eternal crisis in their universes, Valiant can only boast having done so once. (And this was because the company was being refounded two decades after it collapsed!) Characters in the Valiant universe follow long standing arcs, many spanning thousands of years, and switching allegiances as they crossover from one story to another. This setup allows for all kinds of different stories to happen, and characters to be expressed in all manner of situations, without retconning what previously happened. Setting all that aside, the beauty of The Valiant Universe RPG is all in it’s presentation. It’s detailed in its explanations of the setting and characters, and has all the important major characters from Valiant Comics’ story arcs. At the same time, it also includes shorter, easier to digest information via cues. The two ways of presenting this information makes it great for cover-to-cover reading, as well as just scanning and picking out specific information. When I picked this up, I was originally only familiar with Shadowman and Bloodshot, and only had a passing familiarity with X-O Manowar. But, even with just some brief skimming, I was able to get a grasp on Bloodshot’s impact beyond his personal mission, and also found a new favorite arc in the Valiant Universe: Quantum and Woody, the two slapstick superhero brothers that fight each other almost as much as they do the villains! Aaron der Schaedel is the host of an eponymous YouTube channel. On it, he talks about all kinds of different RPG, either slicing through the rules for really dense ones, or shining light on oddities. Aaron would greatly appreciate if you would check out his channel, and subscribe if you like what you see. Picture Reference: https://www.catalystgamelabs.com/valiant/ How do you plan encounters? What follows is the system I use to plan my encounters, sprinkled with stories about other ideas and suggestions on how to plan and make your game the best it can be. 1) All Encounters Are Planned Every encounter is a planned event. Even the random encounters that represent roving monsters or a guard patrol. Encounters happen for a reason. Maybe you’re throwing in some combat for the session, or maybe you’re trying to create tension, or trying to help the party gain experience points, or maybe all of this is to further the story. Hopefully all your encounters will serve to move the story forward, even if they seem random at the time. If all encounters are planned, hat might seem inconsistent with the idea of a ‘random’ encounter though. However, as the DM you have to do work with those random encounters, and even that moment after rolling requires at least a tiny bit of planning. Will the monsters ambush the party? Will they just wander up on them? Or are they roving, looking for dinner, or do they represent guards or guardian beasts? When you create an encounter you either plan it out during your planning session or you do a quick setup in your mind. I find it best to prepare a few hours prior to a game and when I run, I like to have a series of encounters already rolled up to be used in that game session. If they aren’t used, then they can be saved for later sessions, either in another campaign or tweaked and improved for another encounter in the current game at a later level. So, how do you plan the encounter? Most people spend two to three hours planning an adventure for every hour they plan to spend playing. If you are using a pre-written module then this planning time is often used to read the module and adapt it for your players. Few modules just drop into a running campaign, that’s where Adventure Paths are great, since they run for a long time. But, trust me, after you run an AP that ends at 15th level, most groups will want to keep playing. So, you had better have something for them. Now I have heard of a DM who liked to roll a die for the Bestiary he was going to use, and then rolled percentile dice for the page number he was going to use, thus opening up all the possible monsters to be used for in a random encounter. This meant their players could encounter a contract devil, a six-armed demon, a pseudo dragon, a mountain lion, or even a horse. So, what is a mountain lion doing in the desert or in the plains? Why would a six-armed demon or a contract devil be wandering around for a random encounter? My view is that this makes the game seem unreal and often silly. Would you place an ancient red dragon in the arctic guarding a single chest with 20 gp in it? That is just poor planning. 2) Preparing A Curated List To give your game more realism, you need a curated list of adversaries that can be encountered in each region, or area. I am not saying that this list has to be run strictly according to level though; but do you think a pack of wolves would be a match for a tenth level party? They would also be too much for a first level party. Now anyone who goes off adventuring deserves to be challenged and sometimes the best answer to a challenge might be to run away from the encounter; like a first level party against an ancient green dragon. But, there is a problem with that theory: the players trust you and they are there to play, not to run away. So, more often than not they will rush headlong into an encounter they are clearly unprepared for. So, unless you give them a clear sign that they are outmatched, and even if you give them a good hint, they are more likely to run into battle with the expectation that it will be a hard fight, but that they will win. After all, heroes don’t run. So, before you create an encounter list that has a wide range of levels, think about what your players will do. Now you might have a green dragon living in the local woods and the party could be warned. If they go into those woods then let it be upon their heads, but do you really want a TPK (Total Party Kill)? The better idea would be to have the green dragon demand service from the players and get increasing outrageous in her demands until the party finally goes up against her. Plan those encounters so that she doesn’t have a demand each level but she has enough demands to make her bothersome. Also make those encounters with the green dragon meaningful. Green dragons are plotters and planners. Sure, their biggest plan may be for a practical joke, but a dragon lives a long life and like anyone they want to do things with their lives, not just sleep on their treasure horde. Ideally, they want to increase their horde. So, the green dragon is likely to test the players power all while sending them on quests to enrich her horde. 3) Do The Unexpected Of course, you want to do the unexpected in a game. Doing too much of the same old thing will bore the players, so you need to spice things up and you need to provide at least one surprise for the party in each session. One time I took a first level party and told them that they were hired by a village to get rid of a dragon. This was a dangerous beast, it had killed Bob the fighter, and he was the toughest fighter in the village. The dragon had a ransom note delivered that said if he wasn’t paid, he would rampage through the crops and the village was getting desperate. The party seemed reluctant, but they trusted me and went on the mission. One night the saw it rampaging through the crops and spouting off fireballs! The party knew the dragon was real, but they never saw it fly. They tried to track it and saw unusual tracks like it had spikes underneath. A cavalier climbed on top of a house and fired an arrow into the dragon, and it slipped inside the dragon and was lost from sight! Now the party had reasons to suspect that everything wasn’t as it appeared. Frankly, the party didn’t know a dragon from a drake, and neither did the town. Turns out the “dragon” was actually a mechanical dragon that ran on treads. A gnome illusionist was using silent image to make it seem more realistic and he had a fire lizard in a cage in the mouth that would breathe fire whenever he poked it with a stick. The gnome had captured some kobolds and they ran on a treadmill in tandem to make the dragon go forward and the gnome had brakes to turn left or right. It was crude, but it worked. More importantly, it was a fair match for a first level party. For a higher level party you could boost the kobolds into hobgoblins and increase the level of the gnome illusionist and make his illusions better, but it would be harder to pass the encounter off as a real dragon. At that level, the party is likely to have an idea of what a real dragon can do and there are too many things that the fake dragon couldn’t do. Besides, the goal of the encounter was to throw a “dragon” at a first level party and make it a fair fight. 4) How To Avoid Murder Hobos Remember, the primary pattern of the game is for the party to go out, find big scary monsters, kill them, and steal their wealth. This is where the expression “Murder Hobos” comes from. A party of Murder Hobos has no fixed address, no ties to the area they are adventuring though, and no compunction about killing any creature they come across and robbing them. You can recognize murder hobos by their rush to combat. Now, if the party wants to talk first or if they want to roleplay then you may not have a group of murder hobos. If you have a story that is just a string of encounters with little rhyme or reason, then you will breed murder hobos. If you have a compelling story line and the players are doing more than just traveling around and killing things, then you can get the party away from being murder hobos. Your encounters, how you plan them, if they make sense for the area and the level, they are set at will determine how your game runs and what your players do in response to your encounters. DMs who want to rise above the standard game will do things to encourage their players to go beyond being murder hobos and will try to have depth to their adventures; more than one story line, or more than one event happening at a time. 5) The Nonthreatening Encounter Have you ever noticed when you announce an encounter the party all draw their weapons, start preparing spells, wake up those who are sleeping, and get ready for a big fight. When you announce the bushes are moving, or they hear a noise then they will all get ready for a fight. To stop this, throw in a few nonthreatening encounters. They hear a wolf howl, or the wind blows through the bushes. After a few times they will wait for the encounter to more fully resolve itself before they become ready for a fight. This adds an element of reality to your game. I suggest you create a list of non threatening encounters and add them to your encounter tables. Tailor your nonthreatening encounters for various areas and throw them in occasionally. Don’t make them every other encounter or they will grow tiresome. I once had a low-level party exploring a new area. They came across some dragon poo and were curious about the dragon. The ranger analyzed it and made a Survival roll determining it was from a red dragon and from the size, it was a large red dragon. Now the party was a little scared. Still, they went looking for the dragon. Which was not my plan. The dragon scat was supposed to be a non threatening encounter, after all there is very little inside of dragon poo that is going to attack (ignoring the dung beetle). It was the party’s decision to look for the dragon, so I had him flying around. Dragons have sharp eyes; the party was out in the plains, so the dragon easily found them, and he landed in front of them. He didn’t attack, he felt confident that he could easily eat them if they bothered him. He hadn’t seen humans for a while and was bored, so he was willing to talk. They had a roleplay session with the dragon and let it slip that they were from a town that had escaped a planet wide cataclysm. The town had hidden under a massive dome and shifted forward in time. Now the town had dropped the dome and the people were trying to reclaim lands. When the party let it slip that the town was back and not protected, he asked if they would pay protection fees. The party talked some more, and they convinced the red dragon that the town was defenseless and would pay a ransom. So, the dragon thanked them for the information and flew off. When the party got back to town they heard about the massive battle against a huge red dragon and how the Mage’s College had thrown their most powerful mages at the dragon and defeated him. Needless to say the party was happy to hear the dragon hadn’t laid waste to their hometown. But, imagine their horror when they heard his mate was looking for his killers! The point is, this was all a random storyline that started from a nonthreatening encounter. The original idea of the encounter was to show that there were dangerous things outside here and that the party had to be careful. In this case I didn’t mean to throw a dragon at a 4th level party. You never know where things are going to go in the middle of an encounter or what an encounter will lead to, allow some nonthreatening encounters and allow some roleplaying with each encounter so it leads to an evolving story. What do you think about these ideas? What do you think about the idea of curating lists of encounters? What do you think about the idea of nonthreatening encounters? =I would like to hear your observations and opinions in the comments below? I am Daniel Joseph Mello and I am active under that name on the Facebook d20prfsr.com and Pathfinder Gamemasters forum. Feel free to login to Facebook, on of these groups and drop me a line. I have been involved in D&D since 1981 and by the 5th game I was the DM. I have gamed in the Army, in college, and at conventions. I have written tournament level modules for gaming conventions and been writing about D&D on Facebook for over 3 years. I am also a budding fantasy writer. Picture Reference: https://www.deviantart.com/captainharlock-42/art/Encounter-on-Mythos-Island-694383601 https://www.deviantart.com/captainharlock-42 Ah. Recycling old ideas eh Jarod? You hack. I know, I know. But hey, I’ve played a lot more video games over the past few years and in all honesty, a lot of them have been really good. Spider-Man PS4, Dad of Boy, and I finally got my hands on Dishonored 2. However, as I play more and more of these games I keep thinking to myself… “Oh, how cool would that be to implement into next week's session.” So here’s another collection of my little thoughts and ideas. My little adaptations and wishes. 1) The Witcher 3 The Witcher 3 was - and still is - a really damn good game. But the issue with most open world RPG type games is that they’re often single player based where TTRPG’s are often an exercise in group cohesion. As such, the mechanics oftentimes have almost no common group. I say almost for a few reasons. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be writing this. And as much as I would like to say, “We should implement that no matter where you are in the world you can whistle and your horse will be only a few paces away,” I will instead say I think CD Projekt Red created a possible tabletop mechanic in their mutagens. For those who are unaware, Witchers are able to take a part of monsters called Mutagens and implement them into their own biology. It’s a dangerous, albeit interesting process. Not to mention it provides a significant combat advantage. Now, in the case of D&D, Matt Mercer has already created a homebrew class called the Bloodhunter, and one of their subclasses is called the mutant. And while I can in no way deny that Matt’s class is effective and that this idea is implemented very well by him, I will instead make the case for a different style of implementation. Anyone can implement these mutagens into their bodies. The process is dangerous, and there’s a very good chance you can die if you don’t take the proper precautions, but to obtain mutagens, you must have a very specific and expensive tool that requires a trained operator, additionally mutagens can only be taken from monsters and animals that have died within the last ten minutes. Luckily they have a decent shelf life. A month or two. Mutagens are, at their best, unpredictable. And at their worst catastrophic to a mortal’s body. A mutagen taken from a werewolf can do everything from heightening one's senses to a bestial level, to granting one supernatural strength, to simply cursing the subject with lycanthropy. I don’t feel I could make a general outline for the general effects of mutagens on a player character, but I might implement them similar to artifacts in D&D, where when undergoing a mutagenic process you can gain both beneficial and detrimental qualities. I would also say that a player character can only have a few mutagens in their system before it kills them. I would say two would be a good limit. Or if you really want to get crazy, use their constitution modifier (or equivalent) to determine the number of mutagens one can have. 2) God of War (With A Beard) The newest God of War is another gem of a game. I would call it a diamond in the rough, but it’s more of a diamond that’s been put on billboards and shit, because this game was impossible to escape for most of 2018. Everything from the voice acting to the simple yet engaging story, to the rich and glorious worldbuilding was a wonderful ride. In every way. (Fuck the Valkyrie fights my guy. Especially the one in Musphelheim.) But it’s very specifically a video game experience. What on earth can my simple mind take out of this game to apply to a tabletop setting? I hear you asking in order to allow me to transition into the point of this point. The point being Runic Attacks. Yes, this boils down to abilities with cooldowns. Yes, it boils down to everyone having more DPS and status effect capabilities. But what I’m trying to get at is some sort of physical thing that you have to interact with to gain this ability. Sure it could be as simple as a magic item (McGuffin) but let's take a moment to get out of the Box™ and try thinking outside of it. Maybe it’s spirits that the players did a service for who now want to bless them with a conditional ability in which they call upon the magic of nature. Or unknowable beings that force arcane power upon the player so they will use it at a key moment setting a massive domino effect up. Perhaps even a divine gift from the gods for the parties unconditional wholesomeness. There are so many ways to pull out some sort of cooldown ability. Whether or not the reason behind the cooldown is arcane or just some force being a dick is completely up to the GM. 3) The Elder Scrolls: Skyrim Piss. Moan. “What did you take from the game where you’re a god by level 37?” Let's cut to the chase. The Elder Scrolls had a cool idea with Shouts. And while I think player characters could have access to that sort of thing, I don’t think it should be as innate as with the Dragonborn in Skyrim. As mentioned by the GreyBeards learning such power should be dangerous, difficult and slow paced to the point where I think the average player character would learn something close to one or two complete shouts by max level. “Fus Ro Don’t” I hear you yelling out to the heavens. But hear me out. Yes, a lot of the shouts in the game are essential “press to win the fight” buttons. But I feel like there should be a lot more balancing to such things. For example, the call dragon shout shouldn’t exist. Ta Da. Not an issue. Unrelenting Force? More like Unrelenting push your enemies back 50 ft and knock them prone if you have all 3 words understood. Sure this isn’t as adaptable as my previous point with Oblivion. And it tips the power balance in favour of the players. But who’s to say that other creatures and beings can’t learn to shout? After all, if the edgy rogue who was born with no parents can do it, why can’t a vampire who’s lived two thousand years? 4) Tetris I bet you read that title and said; what? Well, as you may have astutely noticed there are no mechanics in Tetris that could possibly fit into any TTRPG that I know of. And furthermore, to make other readers who have come to this page believe that I actually pulled something from a puzzle game where you drop blocks on each other and put it in a TTRPG, I will now type out a recipe for cheesecake brownies. You will need one hundred and seventy grams of cream cheese softened in the microwave. Three-quarters of a teaspoon of baking soda. One eighth a teaspoon of salt ideally kosher salt. Twenty Nine grams of unsweetened cocoa powder. (Or sweetened. I don’t judge.) Two large eggs. One hundred and seventy grams of raw honey. Two tablespoons of vanilla extract. You’ll need the two tablespoons divided. That will become apparent as to why later. A recommended eighty-four grams of semisweet chocolate chips, but as we all know chocolate chips are of course to taste. Seventy-one grams of almond meal or finely ground flour and lastly a non-stick pan. First, preheat your oven to three hundred and twenty-five degrees Fahrenheit. Then in a bowl whisk the eggs together (please note you should attempt to separate the yolk from only one of the eggs and save the whites for the cream cheese mixture and add one-fourth of a cup of water, the honey and one tablespoon of vanilla. Whisk together as well. In a separate bowl whisk together the almond meal or finely ground flour with the cocoa powder, salt, and baking soda. Mix the two mixtures together and stir well. Add chocolate chips and stir again. Then pour the batter into the pan. Now here’s where things get a little weird, you want to take the softened cream cheese and mix in sugar reserved egg white and the last teaspoon of vanilla. Pour that over the brownie mix and spread it about, bake until an inserted toothpick comes out clean (typically about a half an hour.) Let cool and enjoy. 4) (For Real This Time) Assassins Creed Now in this particular instance, I’m selecting more story framing mechanic than an actual game mechanic, however, it does play into the games in a lot of ways. This being the dual settings of the modern day and historical setting. Once again, this is more of an idea than a mechanic so feel free to gloss over this to a certain extent, but I really feel as if there are a lot of ways that new mechanics can flourish in this setting. For example, two separate skill sets. The two separate settings will allow for a lot of room character customization as well as difficult stakes depending on the nature of the dual settings. Of course, the two settings would have to have equal time restrictions. It would have to be very different from the Animus in that the two settings would have to happen simultaneously. However, in large groups, this may quickly become an issue where the party wants to split itself into the group that’s dealing with the one world issue and group that wants to deal with the second world issue. As such, I think that this is best for either very small groups that won’t want to risk splitting, or very large groups that should already be split. There are is a very large well of potential waiting to be tapped into here but I feel like it would be tricky to execute at best and destructive to the experience at worst so keep that in mind should you try to do something like this. 5) Vampyr Another very nice game with a unique concept that finally represented what a game about vampires should really be about. Most of the mechanics in it, however, are similar to a puzzle piece in that they all fit together but not a whole lot of other places. With the exception of the key mechanic. Which is gaining more experience the better you know your victims. Now of course, direct experience is a little bit too much to give to someone just for sniffing around your NPC lore, however, it could definitely be used in a slightly more direct way. This would require a few changes to the base understanding of most games, but should you place your characters in a world in which certain people have power which is inherent and can be stolen, this power could become more accessible to people who know the beings which they’re trying to steal the aforementioned power from. A sort of magical connection that grows as the understanding of the beings grow. Once the being is killed, you could gain a different kind or amount of power based on your knowledge of the being. Murder could be a good idea, but their loved ones would be instilled with the same power as you even if you kill them. In short, you could make a lot of powerful enemies very quickly. There are a lot of places to find inspiration in art. Video games are no exception. There are a hundred different things to yoink and adapt for everyone and it's really kinda cool. Well, that's really an understatement. So go out there and get inspired. Jarod Lalonde is a young roleplayer and writer whose passion for both lead him here. He’s often sarcastic and has a +5 to insult. Dungeons and Dragons is his favorite platform. Although he’s not quite sure if it’s Cthulhu whispering to him in the small hours of the night, or just persistent flashbacks to the Far Realm. Picture Reference: https://www.giantbomb.com/the-witcher-3-wild-hunt/3030-41484/forums/newbie-question-s-a-rpg-and-witcher-newbie-needs-y-1772177/ There are many things which can drive a story, usually a character. Characters drive stories forward by pursuing a goal: their motivation. I am going to discuss in this article what the main types of motivation are, some sub genres of such motivations and how they can be implemented in an RPG setting. 1) Love Love is just any strong positive emotional tie to any thing or person, even if it is displayed negatively or in the wrong way, and as such can drive stories onward with very few other reasons. Love can be more than romance, however every good novel has some degree of this at one point or another. Love could be lust; many nasty deeds are perpetrated under the guise of what is thought to be love. Love is also respect: the king can ask a faithful band of PCs to dispatch a band of rebels camping outside the city limits. Jealousy is a very strong motivator in stories: A wicked witch, madly in love with an NPC or PC, has stolen away the love interest of and the team must go and rescue her. You could begin a campaign with love as the main driving force: the PCs are on a journey north to find the long lost love of their leader, s/he was reported missing one year ago and the PC has been waiting ever since for word if they are alive or dead, well waiting is over s/he has got together a group of friends and has headed out to find out once and for all.Your party could even liberate an object someone has attached feelings to: The old crone who has grown attached to the haunted urn of her dead husband, the child playing with his father’s magic sword. This motivation can get a little overwhelming if you add too many people or things to the inspiration pool, a love triangle is interesting, a love square can have twists but a love dodecahedron is maybe a little too much. 2) Money Money is economy, it is wealth, it is fame, it is everywhere. Money has been the driving force of a few of my starting games, I am adventuring to make money, but then seeded in love motives and power motives. Money could be someone with wealth maintaining it, the lord of these lands has a small workforce and high production needs so works them to death, literally just to make as much profit as he can. It could even be used as a way to show how good someone is, the monk walked the streets handing out what little coin he had to the peasants that littered the town’s dark alleys. It could also buy false loyalty: The Lord pays for the court’s discretion so his son can go about his nefarious doings without hindrance. Money is a good way to get started, have an NPC offer the party fame or wealth in return for an errand, but should evolve into more personal motives unless you are the lord in the example then just get your PCs to burn down his farm and free the workers. 3) Power Power. Those who have it want to keep it, those who don’t, want to take it. Power struggles can make excellent background stories or plot hooks. The king has requested you infiltrate the enemy's fortress and sabotage their weapon supplies. The president has his finger on the big red button ready to start the next galactic war, unless your team can subdue the opposing threat which is forcing his hand. Power can come in a variety of forms from influence in a political setting, power struggles between council members who each have their own agenda, to WMDs in a modern setting, or even a great source of magic in a fantasy game, the crystal banana is a great relic which bestows the holder with the ultimate power of the cosmos, send your party out to obtain or destroy artifacts of significance and let the story unfold. Whatever the combination of motives you use to spur your players onward remember that there is always another waiting round the corner for them to get hooked on, like Borimir in LOTR, he wished the ring of power for himself to protect the home he loved. Two motives in plain sight and a great example of how one leads to the other, his love for Gondor led him to the motivation to obtain the power of the ring. Use motivations as long term or short term goals to keep players eager to play and to keep them coming back for more. Ross Reid is a Scottish roleplayer who is a fan of many a game and system, he has run a game group for the town in which he lives and is currently working on a fantasy novel which has already taken too long. Picture Reference: https://blog.reedsy.com/character-motivation/ There are a lot of different ways to play tabletop games, and to be entirely honest, no singular “correct” way, no matter what some people may tell you. But, for those of you who are interested in creating interesting story-based campaigns, oftentimes the largest hurdle is coming up with an actual story and ways to make it meaningful. In truth, it’s a lot more simple than it seems, so don’t let the Matt Mercer effect get to you. 1) Know Your Players This is a surprisingly simple trick that can net you some pretty rewarding gameplay and roleplay. What keeps a player invested differs from player to player, and as such, it’s key to understand what gets the proverbial motor running behind each one of your players. A nice and easy way to gauge what they want is to ask them to rate the Three Pillars of D&D, which are Roleplaying, Exploration, and Combat. (Please note that these are the official pillars as laid out by WOTC, I would argue there are at least two more, that being Problem Solving and Story Telling, however, you could in theory group storytelling in with roleplaying. But I digress.) If you get your players to rate these things, you’ll have a much easier time leading the group. One of the parties I DM for meets up very sporadically and only for around two hours when we do. As such, a prolonged storytelling experience isn’t nearly as practical as it is with the other group I’m with, who meets bi-weekly for upwards of four hours. I asked both groups what they were looking for and the one very much so wanted much more combat and exploration, while the other prefers roleplaying. This sort of awareness of your players’ expectations are going to make it much easier to plan for them, and to know what will keep them involved in the game. Don’t forget to also ask them what kind of difficulty they’re looking for. I typically run my games on a homebrew critical system, where any critical can in theory instantly kill a character or monster. For people who are looking for a more relaxed game, this sort of overhanging threat of death at any moment might be a bit too much, same goes for players who are looking for a more character driven experience. 2) Create Meaningful Stakes People are inherently selfish, to a certain extent anyway. As such, saying “the world is in danger” often isn’t good enough to motivate players to get into the mood. Besides, if it’s that important won’t some other, far more legendary and powerful group be dealing with this? (Don’t get me wrong, writing a campaign of world-shattering importance is totally alright if that’s what your players are looking for. See point 1.) I find that smaller, more personalized stakes usually motivate parties best, and can almost always be a good way to introduce a larger plot. Starting with something as simple as a character’s family heirloom being stolen, or the wizard’s spellbook being mixed with a different wizard’s, or the mysterious death of a childhood friend or mentor can all open the door into building a deeper narrative and leading into what you want to be the main plot, by making the players already attached to some of the characters you implement. This can feel a bit too general to get a good handle on, but the best way to do this is to know your players. If combat is what they’re looking for, then toppling a tyrannical king via military dominance might be the way to go and the stakes can be their own lives, and the lives of their families. If they’re looking to explore, have them sent out to discover new lands or gather artifacts, with some sort of rival adventurer party trying to steal their prize before them. Alternatively, perhaps one of the players decided to try to learn a new language through an ancient magic game, but if they fail to keep up with the lessons a large green owl will kidnap their family. 3) Enjoy What You Make This probably sounds cliché, but if you don’t enjoy writing the campaign, your players won’t enjoy playing it. This is honestly true of most writing endeavors, however, I find it rings especially true in a table-top environment. This is, after all, a game. And games are meant to be fun for everyone. Including the GM. If you want to make a pirate based adventure, then make one. You’re better off making it and trying to make it work than making something you don’t have any interest in. The reason behind this is that quality is usually tied rather closely to effort, but one thing that is often overlooked in quality is passion. Because passion is also very closely tied to effort. It’s like a little reduce, reuse, recycle sign, but for writing your tabletop campaign. As the GM it’s very easy to forget that you are just as much a player as the rest of the people at your table, and if you’re not enjoying the content at the table, the table will undoubtedly suffer because of it. When I first started DMing, I thought of it as a responsibility, and while that is partially true, it’s not all that it is. It’s having fun with traps and putting people in strange situations and seeing how they react. It’s messing around with your friends and describing a goblin named Tinkle for twenty minutes until the barbarian kills him. It’s exploring, it’s roleplaying and its combat -- oh goddamnit. If there’s one thing to take away from this article it’s that if you feel you’re writing your campaign right, then you probably are. Everyone's table is different from another and in all honesty, the most important part is having fun. As mentioned before, this is a game. Jarod Lalonde is a young roleplayer and writer whose passion for both lead him here. He’s often sarcastic and has a +5 to insult. Dungeons and Dragons is his favorite platform. Although he’s not quite sure if it’s Cthulhu whispering to him in the small hours of the night, or just persistent flashbacks to the Far Realm. Picture Reference: https://geekandsundry.com/gms-3-tips-to-help-you-run-one-shots-like-a-pro/ A friend is currently running a kickstarter for his wild west roleplaying game Ballad of the Pistolero. Last time I looked the game was just over one third funded. By a strange coincidence I am also working on a wild west themed roleplaying game and the two of us produce games that are about as far apart as one could get. Mine is more fast paced cinematic action of Saturday morning Lone Ranger and Casey Jones. Ballad of the Pistolero is akin to the Old West of fiction from The Searchers, to The Good the Bad and the Ugly, and Red Dead Redemption. On December 31st I pulled my Indiegogo crowdfunding project, a matter of hours before it went live. I had created all of the assets for it right down to video trailers. I decided that crowdfunding was not the way I wanted to go. What I have seen in 2019 has only reinforced by opinion that Kickstarters are not necessarily the ‘good thing’ for games that they are portrayed as. If you had ambitions to write your own RPG and fund it through a kickstarter then you may be interested in my reservations. Maybe you will look at them, take them on board and address the concerns to your own satisfaction. At the very least your business plan will be a little bit better and stronger for having looked at potential problems, and thereafter having a solution in place should I be right. 1) Where Do Your Sales Come From? The most basic kickstarter or crowdfunder is based on, pledge money and get advance access to the final game. In effect it is a pre-order system. There are normally tiers of rewards and the more you pledge the more you get. Lower tiers offer PDF copies of the final game and then higher tiers bundle in printed rules and even hardback editions. So why is this a problem? The problem is that if you have a large number of pre-orders, even if everyone you know, and everyone they know, that has any interest in your game has it on pre-order where are future sales going to come from? 2) You Don’t Get What You See If you have a pledge target of $3,000 and you hit $3,000, you do not get $3,000. There are two big slices that get taken out before you get to spend your war chest. The first is the platform fees. Kickstarter and Indiegogo are not charities. They exist to make money and they are going to take a typical 8% of the total pledged. Then there is tax. The money pledged is taxable income and the tax man/woman is going to take their slice. After those two a $3,000 target leaves you with little over $2,000 to actually spend on finishing your game. 3) Fulfilled By Drivethru This is not OneBookShelf’s fault in any way but a great number of kickstarters are fulfilled via Drivethrrpg.com. What this means is that they will handle sending out all the PDFs and eventual printed books for you. You upload your supporters list with what needs to be dispatched and they do the rest. You then just send them the money for any printing and delivery. So where is the problem you ask? The problem as such is not with the fulfillment (that is a great service) but with the way that OneBookShelf and DriveThruRPG rank games. They only count the games that people pay money for. A game that sold one copy for a single cent will outrank a game that has a million free downloads. Therein lies the problem, all your sales were pre-orders and the money doesn’t go through the tills, so to speak. You could send out a thousand copies of your game and it will be nowhere on the popularity rankings. 4) The Real Cost Of Stretch Goals Many kickstarters and Indiegogo campaigns have additional rewards if they exceed their initial goals. You may think you need $3,000 to finish your game, but what if you raise $5,000 or $10,000? You may think that it is a nice problem to have, and in some ways it is. Where the problems start is with the danger of over committing yourself and unforeseen expenses. Along with this is the sheer production time. You probably have your game already written before you even started your kickstarter, but what if you are now committed to producing a GM’s screen and ten adventures? Your production queue now extends months further into the future and you will want to send out all these things at once to your backers to save on post and packaging. Suddenly, you have a big lag between completing your game and sending out the goods to your backers. This also touches on that ‘future sales’ issue. If everyone already owns everything, do they need to buy more? If there are unexpected expenses with any of these stretch goals, like your artist ups their rates as they didn’t realise the project was going to take up so much of their time, you cannot go back to the backers and ask for more money. 5) Natural Born Failure In many respects Kickstarters are popularity contests. It is not the best games that get funded, it is the game designers with the most social muscle who can get the word out about the game. Sure, great art helps. A game trailer video helps. If no one thinks to search for you kickstarter though, no one is going to see or read about it. You need to shout it from the tree tops, figuratively speaking and for that you need a big audience. If you kickstarter doesn’t succeed then your game has started life as a ‘failed’ kickstarter. If you try again, your profile shows how many campaigns you have tried and how many succeeded. Starting life as a failure is not exactly auspicious. Trying to fund a new game is always going to involve an element of risk. At the time of writing there were 525 tabletop role playing games looking for funding and another 20 on Indiegogo all vying for your money and support. If you can make it work for your game, that’s great, but that is against a backdrop of John Wick Presents, who raised $1.3M for 7th Sea 2nd Edition, being unable to deliver. The company laid off staff and push back delivery time but could not avoid the eventual death of John Wick Presents, in March, when it was gobbled up by Chaosium Inc. If that is what success looks like, it could be time to reevaluate one’s goals! There are success stories out there. There must be or Kickstarters would never have caught on, but there is a vested interest to publicise the success stories to make pledgers trust the platform. Games publishers want to tell the world about their successful campaigns as it makes the game look popular and successful. As for my little wild west game, it is out on Drivethrurpg as a free to download playtest edition and quickstart. So far it has had 325 downloads and more daily. Maybe, just maybe the number of people who have downloaded the game will be my audience and I may go for a kickstarter in the end but I probably won’t. I think I would rather take my chances in the general marketplace and avoid the worry. Peter Rudin-Burgess is a gamer, game designer, and blogger. When not writing his own games he creates supplements for other peoples to sell on DriveThruRPG. His current obsessions are Shadow of the Demon Lord, 7th Sea 2nd Edition, and Zweihander. Cover image copyright Peter Rudin-Burgess |

All blog materials created and developed by the staff here at High Level Games Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed