|

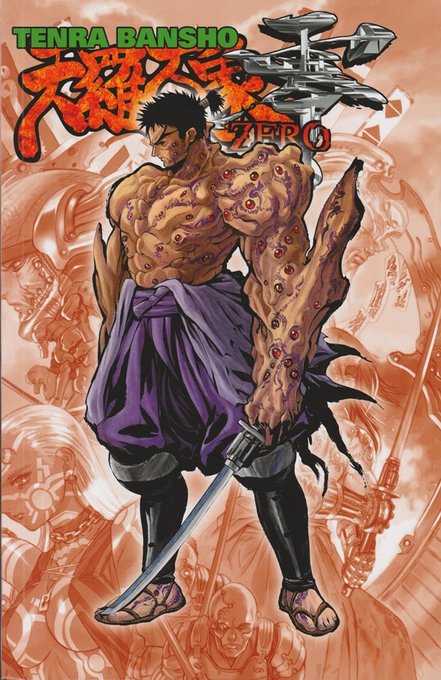

My earliest RPG experiences were with Dungeons & Dragons 3.5, 4e, and Pathfinder. These are (each in their own right) wonderful games, full of arcane character options and high-powered tactical abilities that make it fun to build characters and fight monsters. However, while I have nothing against them personally, these are games I would have little to no interest in ever playing again and certainly never GMing again. This is in part because playing only those games gave me a narrow perception of what tabletop RPGs can be. Even D&D 5th edition, while more streamlined, is still far from my ideal game. I don’t mean to incite anyone to anger, again I have nothing against it personally, but for anyone with any interest in this artistic medium, it’s important to recognize that there are other kinds of games with other kinds of assumptions. With that knowledge, one can best leverage the strengths of a given system, or find the system best suited to a given game or to their preferred style, or bring aspects from one system to another. With that in mind, here are four games that changed how I think about tabletop RPGs. 1) Tenra Bansho Zero This is a Japanese tabletop roleplaying game, one of the few that has been translated into English, and one of the first non-d20 games I ever read, although unfortunately I still have not played it. I would like to play it one day, but even if I never do, even just reading it opened up my mind to new ways to think about tabletop RPG mechanics. The setting is a science-fantasy alternate universe based heavily on Japanese culture, history, and mythology. It explores subjects such as the introduction of Buddhism into Japanese culture and its relationship with Shintoism, the conflict between the indigenous peoples of Japan and the ethnic Japanese, and the psychological impact of transhumanism through body horror. The biggest hook of the system, to me, was the karma mechanic. During character creation, you may accrue karma points to give your character stat boosts or special abilities, and karma can also be spent in-game to succeed when you would otherwise fail or do things that would normally be impossible, a sort of cinematic “anime-mode.” However, if you accrue enough karma, you become an asura, a demon, and your character is taken away from you to become an antagonistic NPC. Characters have a series of personal goals, and accruing these goals allows you to accrue points which can be converted to karma, but also resolving these goals allows you to relieve karma. While the mechanics in games like D&D 5e tend to focus on combat, the idea of using game mechanics to reflect a narrative or philosophical construct radically changed how I thought about what tabletop RPGs can be. 2) Narrative / Story Games (E.g. Apocalypse World, Dungeon World, FATE) Narrative or story games are generally defined as systems that are simple, flexible, and intended to facilitate a particular kind of narrative. There are some contentions around the usage and definitions of these terms, but for the purpose of this article I think this is a useful way of thinking of these games. FATE uses a simple and customizable skill pyramid as the skeleton of all of its mechanics. Characters can effectively do anything it would make sense for them to be able to do from a narrative perspective by rolling a relevant skill. They may spending FATE points on aspects, short descriptors that interact with the environment or narrative, to give themselves benefits to their rolls. Apocalypse World, Dungeon World, and other Powered by the Apocalypse (PbtA) games are constructed for a very specific setting or genre. Actions are engaged with moves, meant to facilitate character interaction or interaction with the narrative. These actions are resolved with given degrees of success and failure on the roll that always keep the game moving forward. Both can be easily modified and are designed to be modified, but I like FATE Core for one-shots since it’s so simple and has a cinematic, fail-forward approach to gaming. I’m still wrapping my head around PbtA games, sometimes I feel like the mechanics in those games just get in the way of me doing what I would be doing anyway, but for someone with no experience with this style of play, these games can serve as good instructions for how to tell compelling narratives in a tabletop RPG. 3) Cypher System (Particularly Numenera) Cypher system, initially created for the game Numenera, was designed by Monte Cook, one of the lead designers of D&D 3rd edition. He is a somewhat controversial figure in tabletop, but regardless of what you think of him as a person or businessperson, he is undoubtedly one of the most influential figures in tabletop. Cypher is hands-down my favorite system, and while it seems to have carved a niche for itself, I think it’s a shame that it’s not more popular. Monte has stated that he designed the system as a way to correct for some of what he perceives as mistakes he made with D&D 3rd edition, and it feels as a result like a blend of the aforementioned narrativist games and traditional D&D, with some unique mechanics I have not seen anywhere else. It is super easy to run as a GM, with most obstacles or enemies being reducible to a single number. It also finds a strong balance between a wide variety of relatively deep character options that make character building fun, but does not pigeon-hole you into specific builds or become so deep or complex as to stifle storytelling. Many people seem to struggle with its three stat-pool system, which acts effectively as HP and ability points which can be spent to lower the difficulty of tasks as resolved by a d20 roll, but I think if you can wrap your head around it, it’s one of the most distinct and flexible mechanics of any RPG (although that may require a post unto itself). The Numenera setting is also excellent. The book is packed full of beautiful art, the system is embedded within the game so the Cypher core book is not required, and the setting itself is flexible and open to interpretation. It’s a post-post-apocalyptic, far-future science fantasy setting, one where ancient and advanced technologies indistinguishable from magic are utilized by a medieval world that has sprung up in this glorious refuse. Besides being a perfectly weird setting in itself, it also explains how to build a weird world and tell stories within such a setting in a way that really changed how I thought about worldbuilding. Despite having read so many science fantasy novels, I don’t think I really understood what makes weird worlds work until reading Numenera. 4) OSR (e.g. Lamentations of the Flame Princess, Dungeon Crawl Classics, Sharp Swords & Sinister Spells) OSR, or old school renaissance (some people prefer to say revival), refers to retro-clones of old school (pre-3rd edition) D&D or games derived from those systems. OSR is defined by a complex and highly debated set of properties and sensibilities, but is usually associated with player skill over character skill, intentional lack of game balance, high challenge, low heroics, high mortality, randomization, and GM “rulings” over rules. While once narrow in scope, this term has more recently been associated with games that share these sensibilities but are not strictly tied to old school D&D. Popular examples of OSR games include the weird 17th century-esque Lamentations of the Flame Princess, the slightly more mechanically deep Dungeon Crawl Classics, and more recent games like Into the Odd, Maze Rats, and Sharp Swords & Sinister Spells, which are novel systems in their own right. Honestly, OSR is not my preferred style of play, but it is certainly an interesting way to think about tabletop gaming. It is distinct from the crunchier, more tactical games like D&D 3.X, Pathfinder, and D&D 5e, and also from the narrative games. It is worthwhile to understand the history of the medium, and also to explore this new branch of an old style of game, and if nothing else, it has attracted a scene of writers and artists doing really weird, avant garde, novel worldbuilding and game designing. Quite frankly I think it’s the most interesting work in tabletop gaming at the moment. This is by no means a comprehensive list of every game you should play (or read), but these are a handful of games or game-types that have informed how I think about tabletop RPGs. I know I spend a lot of time in my articles talking about worldbuilding, and I consider myself a worldbuilder first and foremost, but game mechanics can inform a setting. Two games set in Forgotten Realms or some other traditional fantasy setting can feel completely different depending on whether you’re playing the heroic, tactical D&D 5e, or playing the deadly OSR games which encourage roguish behavior. A karma system like Tenra Bansho Zero allows you to explore philosophical conceits within the game itself. Narrative games allow you to tell a collaborative genre story without the game mechanics getting in the way of the story. Systems like Cypher may give you the best of all worlds, and a setting book like Numenera may make you a better worldbuilder and GM. No need to trash your D&D 5e or Pathfinder books, but if you’ve ever thought, “I wonder what else I can do?”, give some of these games a look! Max Cantor is a graduate student and data analyst, whose love of all things science fiction, fantasy, and weird has inspired him to build worlds. He writes a blog called Weird & Wonderful Worlds and hopes people will use or be inspired by his ideas! Picture Reference: https://cdn.pixabay.com/photo/2016/07/07/16/46/roll-the-dice-1502706_1280.jpg  Before we get to what was advertised on the tin, I’m told I need to call your attention to our Patreon. What I would next like to bring your attention to is that this website currently doesn’t run ads. (It’s true! Trust me, turn off your ad-blocker for a second!) We don’t like to run ads because frankly, they can get really annoying, especially if they’re irrelevant. Unfortunately, good web-hosting isn’t free. So if you could find it in your heart to contribute to our Patreon, you would not only be helping us keep this site ad-free, but you’d also be helping keep it ad free for your fellow fans and gamers as well. There’s also some other neat stuff you’ll get access to if you contribute, too! And now, our feature presentation! Awhile back, I wrote about some of the games from Japan that we in the English speaking world now have access to. All of them were unique in their own ways, but none quite as much as Tenra Bansho Zero. It has some of your standard fare you could expect out of most TRPGs. Things like dice pools, class based character creation, and combining attributes and skills together for rolls. But that’s all basic stuff: Tenra Bansho Zero offers a great deal more, such as a unique setting based on the Warring States period of Japan, as well as this set of really cool mechanics they call “The Karma System.” 1. Fates Fates are simultaneously one of the smaller parts of Tenra Bansho Zero, and the heart of everything that makes it unique. In short, they’re what your character cares about, be they other characters, their attitudes regarding certain subjects, or things they simply refuse to do. Every Fate is rated from 2 to 5, which signifies how strongly a character feels about the given Fate. Most importantly, each Fate is also known to all other players. Motives aren’t kept secret here. This isn’t necessarily a novel mechanic on it’s own. In fact, many narrative-based games have similar mechanics to this. Though how it integrates with everything else is what makes it noteworthy. 2. Aiki Aiki are tokens given to players who roleplay well, either by being entertaining to the rest of the group, or following their character’s Fates. These can then be used for various temporary bonuses and effects, such as gaining extra dice or temporary skill points, or calling another character (player or NPC) into the current scene. What sets this aside from similar systems in other games is that Aiki can be awarded by ANYBODY, not just the GM. Your aim when acquiring Aiki isn’t just to entertain the GM, you’re also trying to entertain everybody at the table! Additionally, Aiki are used to acquire more Fates, as well as for making Fate Rolls, which is how you acquire our next topic: Kiai. 3. Kiai Kiai is functionally very similar to Aiki. Everything that you can do with Kiai, you can also do with Aiki. Though a character with higher rated Fates will be able to turn a few chits of Aiki into many times more points of Kiai, making Kiai a much more effective way of improving a character or gaining dice bonuses. Fate Rolls are the only way to generate Kiai, and they can only be done under certain circumstances. The first of these being that the player needs to spend an Aiki chit to make the roll. The second being that either a character’s Fate must be immediately relevant to what’s currently going on in game, or it needs to be during the Intermission phase of the game. The player then rolls a number of d6 equal to their character’s Empathy attribute, and each die that shows a number below the rating of the Fate being rolled for generates one point of Kiai. While Kiai can be more numerous than Aiki, they do have one drawback: every spent point of Kiai eventually converts into Karma. 4. Karma Karma is gained in many ways in Tenra Bansho Zero. First and foremost, it’s gained during character creation: every template for building your character has an associated Karma cost. Karma is also raised when acquiring certain weapons and equipment at any point in the game. (Most notably: Soul Gems. Powerful magic orbs used as ammo for certain weapons, or embedded into people to grant them mystical powers.) Spent Kiai also converts to Karma during the aforementioned Intermissions; breaks in gameplay where major, off-screen developments can happen. It’s also worth noting that everything mentioned thus far easily makes it so that two characters, even at character creation, can have wildly different Karma values. If a character’s Karma is ever 108 by the end of an intermission, they become a monster that is obsessed with their Fates known as an Asura. At this point, the GM takes that player’s character sheet, tells them to make a new character, and it becomes entirely possible that this character is now an enemy to everybody at the table. This then begs the question: can one lower their Karma? And if so, how? Once again, Fates are the answer. Another event that happens during Intermissions is that players can change and eliminate their character’s Fates, causing a decrease in their total Karma, as well as a shift in what the character thinks, feels, and believes. And thus the cycle is complete: your Fates grant you power, that power grants you Karma, and letting go of your Fates is what releases you from the dangers of Karma. So with all that said, we have the four components of Tenra Bansho Zero’s Fate System. This set of rules is one of the things that makes Tenra Bansho Zero a truly unique game. It rewards players who use their character to affect the world around them, or to at least entertain those also playing. Additionally, it provides a vehicle for characters to be more dynamic. The Fate System in Tenra Bansho Zero shows us, above all else, how even if we can identify and describe an individual game mechanic, it’s the sum of all these mechanics that make a game what it is. Aaron der Schaedel isn’t really an expert on Japanese TRPGs, he just knows a lot more about them than your average person. He also wants to encourage people to try out and learn more games, and has compiled a list of helpful advice on the subject, which you can find here. Pic Reference: http://www.tenra-rpg.com/  I am both a fan of table-top games and Japanese pop-culture. The first instance where I got really absorbed into the table-top fandom was, oddly enough, at an anime convention. I was enamored with all the new games I previously never knew existed, but one thing DID irk me about that scenario: even though we were at a convention celebrating Japanese pop-culture, none of the games I saw were of Japanese origin! After that, I dedicated myself to reconciling this discrepancy, and have learned about a great deal of Japanese table-top games. With all that said, allow me to share with you some of the RPGs from Japan I’ve learned about -- specifically, those that have been officially published in English! 5) MAID Let’s get the weird one out of the way first. MAID is exactly what its name implies: a game about maids in service of their master, creepy connotations optional. In truth, this is a game that’s more about random change and crazy coincidences. MAID is played primarily through random charts and d6s. At character creation, everything from characters stats, why they’re in the master’s employ, and several other strange quirks (such as being a robot, a demon, or a cross dresser) and even the color of their outfit is determined entirely at random. This is also an odd instance of an RPG that was designed to be competitive. Whenever a character completes a task set forth by the master, they gain Favor. Favor can be used to raise stats, or cause a random event to occur, though whoever has the most unused Favor at the end of the session is declared winner. As stated earlier, this game is weird, even when you overlook some of the suggestive themes. On the bright side, even in Japan this game is unusual. 4) Double Cross Double Cross is a game set in an alternate universe version of our modern world, where a phenomenon known as the “Renegade Virus” has infected nearly everyone. While it normally remains dormant in its host, the 1 in 5 people who are active hosts have tremendous powers. Some use these powers to their own nefarious ends, and others to foil the plans of those who would do evil with these powers. Unfortunately, all who rely on these powers eventually go mad. Mechanically, Double Cross is a d10 dicepool game, and the meat of character customization is in deciding how the Renegade Virus manifests in your character. You gain up to three “Syndromes” which determine what powers are available to you, as well as how much you can develop those powers. What truly makes this game unique is the game’s “Encroachment Rate” system, a representation of how much the Renegade Virus has taken over a character. This rises not only every time a character uses a power, but also whenever they so much as appear in a scene! Encroachment Rate is lowered at the end of every session, though, based on how many other characters a PC has connections to. This gives the game a unique dynamic where players have to make their entrances into a scene count, either by contributing to the party’s end goal, or by meaningfully interacting with NPCs. 3) Golden Sky Stories Golden Sky Stories is part of a Japanese style of game referred to as “Honobono,” a word that can translate to “Heartwarming.” The premise of Golden Sky Stories is that the players are “Henge,” shapeshifting animal spirits, in a rural town on the Japanese countryside, helping the villagers with their problems. (Or perhaps cause mischief for them!) Characters in this game have different powers based on what sort of animal they are, as well as what weaknesses they take for their animal type, such as Fox’s not being able to resist the temptation of fried tofu. This, in addition to the universal ability of all henge to take on human form in addition to their animal one. Resorting to violence is actively punished in Golden Sky Stories; any time a character does so, it causes all other characters to fear them, severing any sort of connections they have. This is not a good thing, since connections to other characters is how a character gains the energy necessary to use their powers and temporarily raise their stats Another interesting thing to note about this game is that it doesn’t use dice. This game instead relies on temporarily raising stats to overcome challenges, in either the form of the GM setting a target number, or a bidding war between two characters. The end result is that despite their wild differences, Golden Sky Stories creates a similar sort of motivation as Double Cross: if you don’t interact with the world, you will accomplish nothing. 2) Ryuutama Ryuutama is yet another Honobono game, affectionately described by its translators as “Hayao Miyazaki’s Oregon Trail,” though I personally like to describe it as a complete inversion of Dungeons and Dragons: instead of being a game of Wizards and Warriors searching for treasure by slaying monsters, it’s about Merchants and Minstrels seeing the world. Travel is a major theme in Ryuutama; the player characters are a party of villagers that, as I’ve said earlier, that are traveling the world. Most of this game’s mechanics revolve around traveling; primarily being sure you have enough food and water to survive the journey, as well as getting the right gear to make the trip easier. The player characters, after gearing up and setting out on their journey, as followed by a dragon-human hybrid known as a Ryuujin who records the exploits of these travellers. This character is specifically meant to be a character of the GM, complete with special abilities of their own. And for any players who are accustomed to their RPGs being fight simulators, unlike Golden Sky Stories, Ryuutama DOES include a combat sub-system. 1) Tenra Bansho Zero Even when compared to other Japanese games, Tenra Bansho Zero is simply an all around unique game. In the creator’s words, it’s a “Hyper-Asian” setting; it’s set in a world known as Tenra, an alternate universe version of Warring States Period Japan where magic is real, and technology continued to progress to the point where giant robots and cyborgs were reality. The wild ride doesn’t stop there, though. Not only do you have ninjas, cyborgs, sorcerer summoners, and warrior monks all fighting on the same battlefields as giant robots and cyborgs, but when creating your character, it’s entirely possible to mix several of these different archetypes. And while wacky character archetypes is great fun, what truly makes Tenra Bansho Zero a magnificent game is it’s Karma system. The short version of how it works is this: when you make your character, you decide on what’s important to them and write them down as “Fates.” Over the course of play, if you’re acting out these Fates, or just generally being entertaining, anybody else at the table can award you an “Aiki Chit.” These chits can either be used immediately for special bonuses, or they can be saved for a “Fate Roll” later on. If you save them for a Fate Roll, you can gain Kiai, which like Aiki Chits can be used for temporary bonuses or to raise your character’s abilities. Using Kiai, though, causes your character to gain Karma. Karma is not good, having over 108 Karma makes your character unplayable as they turn into an obsessive monster known as an Asura. Karma can be removed by either removing or changing your character's Fates at designated times during the game. Even more succinctly, Tenra Bansho Zero is a game where you CAN have the biggest and toughest character in the game, but it doesn’t mean too much if you’re not willing to do anything interesting with that power. Japan has a pretty unique take on the table-top RPG genre, as evidenced by what I’ve shown here. It’s a much more theatrical affair, that doesn’t just ask for players to roleplay entertainingly, but sometimes DEMANDS it. The world of Japanese table-top games is a big one, and while I’ve only scratched the surface here, this is still as good of a place as any to start. And if one of these game’s piqued your curiosity, but you’re a little anxious about teaching yourself a new game, I’ve got you covered for that, too. Aaron der Schaedel isn’t by any means the most knowledgeable on Japan’s table-top gaming culture. He’s just very vocal about what he does know, which is still a lot. Rumor has it he even does live presentations about these sorts of things at conventions! |

All blog materials created and developed by the staff here at High Level Games Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed