|

For the longest time, I spent my time in the roleplaying game fandom on its fringes. The only community I was an active participant in was one dedicated to games from Japan. Don’t get me wrong, the folks in that community are great, but after an ugly encounter with a newcomer (that stemmed partly from a lack of tact on my part), I figured it was time to go out and refamiliarize myself with the larger RPG fandom.

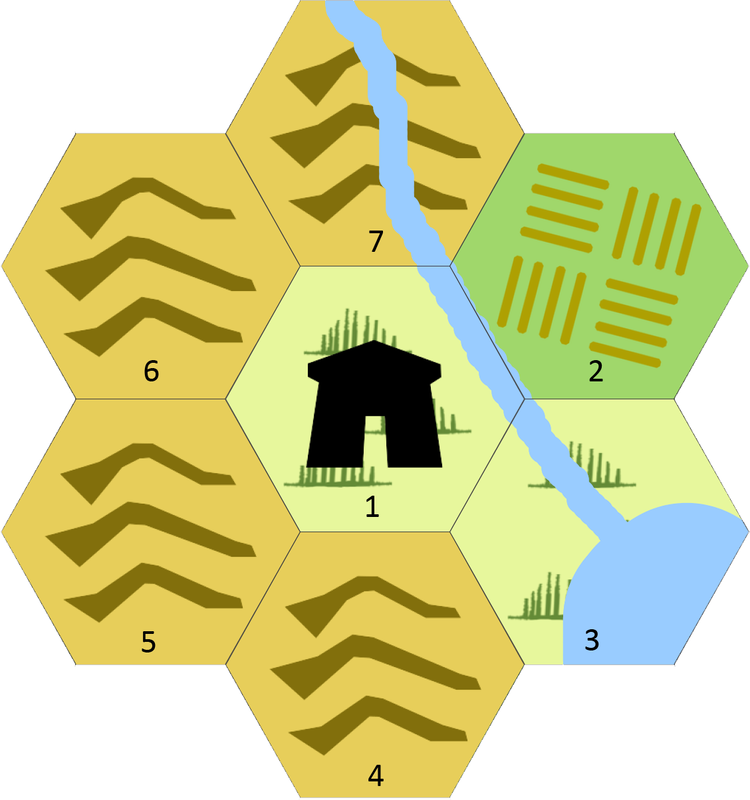

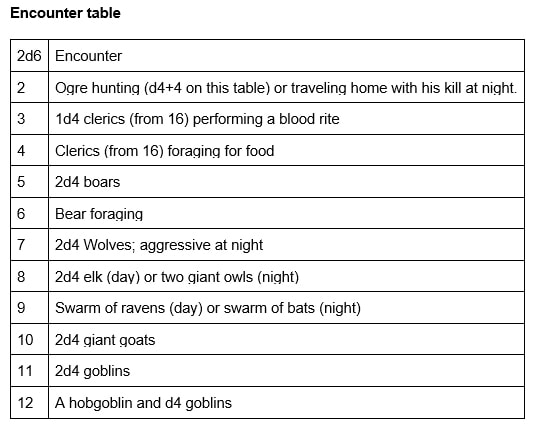

I spent the following months becoming more active in other Discord servers, as well as connecting with other folks of the TTRPG Twitter-sphere, and even attending some Dungeons and Dragons panels at the Kentokyocon anime convention in Lexington, Kentucky. I’ve always known I was an oddity and the worst possible example of what’s normal, so this mission was to give myself a point of comparison: to better understand what IS normal. What I learned in that time will no doubt be obvious to some of you, but I still believe it bears saying, if only so there’s a snapshot of the scene at this point in time.Since this is still an article about a leisure time activity, though, I believe it deserves an element of whimsy, so I will be including some dragon slaying metaphors. With all that said, I present to you all: 5 Things I Learned Reconnecting With The D&D Fandom! 1) Dungeons and Dragons Is Still King Of The Hoard Attention and participation are gold, jewels, and other fine treasures, while Dungeons and Dragons is a dragon sitting atop a giant pile of it. The statistics that Roll20 used to publish on a yearly basis is the largest set of data we have on what games are being played. It’s far from a perfect dataset, since it’s only one platform, and it doesn’t list every possible game one could use the platform for, nor allow users to “fill in the blank” if their game isn’t listed. Rigors of the data aside, it does paint an unsurprising picture of the top dog: Dungeons and Dragons or some derivative thereof. A quick look through the #ttrpg tag in Twitter adds to this picture: even though the tag is an acronym for “tabletop roleplaying game,” much of what you’ll find is geared towards Dungeons and Dragons. From pictures of the 7 piece polyhedral set, fantasy artwork, and memes alluding to situations that could only happen in D&D. For a tag that uses such a broad term, it certainly has a narrow scope. One of the next biggest franchises in the RPG fandom, Shadowrun, doesn’t look like it’d fit in with this tag. It’s a near future, cyberpunk, urban fantasy, it only uses d6s, and while magic items and talismans exist, they’re almost exclusively used by magical characters. 2) There Is A Hope For A Dragon Slayer Be they driven by curiosity, or a desire to see their world be the best version of itself, they want the dragon slain, so that the hoard can be shared by all. This, I had in common with some of them all along. If you dig around enough in some of the dialogues that take place on Twitter, you will occasionally find a few dissenting voices: people who want more attention to be paid to other RPGs besides Dungeons and Dragons, and others who would gladly oblige them. Their reasons vary and range from an acknowledgement of D&D’s flaws, to wistful expressions of not wanting to miss out on everything that the RPG fandom has to offer. These are the people I naturally gravitated towards, given my background of having divorced myself from D&D many years ago. The community I was in had a very strong distaste for Dungeons and Dragons; we were aware of the flaws, and we knew they could be fixed, we in fact played other games that did! Our frustrations lead to some fairly cruel jokes we would tell at the expense of Dungeons and Dragons players, often in the format of “Why would you play that game? You can get the exact same experience by playing Pathfinder with these splatbooks and my homebrew system.” Though, stepping outside of the bubble I was in made me realize: it may not necessarily be out of stubbornness that people cling to Dungeons and Dragons; but rather just not knowing how great other games can be. I had always known this might’ve been the case, but it was a different thing to see it for myself. 3) Everybody Wants To Be The Dragon Slayer Many are confident in their abilities, believing they’ll be the one to slay the dragon, or that their efforts will contribute to its downfall. The indie roleplaying game scene is huge. There’s numerous new games, splatbooks, and scenarios everywhere, created by all kinds of people. There are also scores of people recording and broadcasting their own games for the enjoyment of others. Many with aspirations of being the next big voice. These modern days of the Internet Age also constitute a creative Golden Age: we have a huge collection of information, tutorials, and software available to us at our fingertips. If you have a computer and an internet connection, you can feasibly learn how to make anything. The Dungeons and Dragons fandom is just another example of this. If you dig deep enough, you can find those same people who want D&D to be taken down a peg, wanting to rally people together so they can collectively have their fair share of the market. Whenever one of these calls goes out, it usually ends the same way: parties show up talking about what they’re doing to that end, how they’re different and how they believe they’re going to be the one to make a difference. 4) Conformity Is What The Dragon Wants (And Gets) The dragon has its methods for maintaining its hoard: let a few people take from it, and collect tribute from others. Then the dragon won’t need to fight the people or try to stop them, but rather let human nature defend the dragon’s hoard. There’s a lot of market forces at work that keep Dungeons and Dragons on top. They’re the biggest name in the industry, and for better or worse, being that big reinforces its top position. Anybody who wants to make some kind of living creating for the RPG fandom will likely need to make something catering to Dungeons and Dragons. The predictability of computer algorithms makes it impossible to be discovered if you’re not on a known tag or keyword, and if your end goal is to make money somehow, your best bet is to aim for the biggest market share and hope you’re noticed. One of the major selling points of Dungeons and Dragons is the sheer volume of content there is; when one sees so much, it’s easy to come to believe you don’t need anything else. Somebody else likely has already made what you’re looking for. Wizards has even created a marketplace specifically for content for D&D and D&D alone. Most damning to those that would want to topple D&D is this: humans are creatures of conformity. Being like everybody else is soothing to us, even if it’s ultimately detrimental. Newcomers come in, see it’s all D&D, and come to believe D&D is all there is, or that anything else is in the tabletop RPG fandom going to be similar to D&D. (Even though D&D’s genre, Dungeon Crawl Fantasy, is fairly unique in what it does.) It also leads people to believe that since D&D is a complex game with several specific rulings that must be known, every game is. That since most people play D&D before they run it, they must play other games before they can run it. That since so much of the onus is on the DM, the same must be true in every other game. This leads to trepidation that is then soothed by remaining in line with what’s familiar, even if it ultimately falls short. 5) There’s More Than One Dragon The dragons are everywhere, and thrive in this world. Wherever there is treasure to hoard, there is a dragon to guard it jealously, often with the same tactics. I originally set out to write an article about roleplaying games and human nature when we gather around media. As I added to these points, I realized that a lot of what I had seen as I put myself back out there into the D&D world were things I had seen everywhere else. Even though comics are now mainstream and cool, it’s weird to like anything that isn’t DC or Marvel, and if there’s any issue that needs to be addressed in the comics fandom, the onus is only placed on those two juggernauts to resolve it. (Even if a different company had already taken steps to address it; it may as well not exist.) The only way to be recognized as a fan or critic of comics is to work with the larger companies; it might be possible to claw your way to recognition through other means, but the faster route is often to get lucky placing your bets in the oversaturated market. This is a phenomenon across all kinds of media, and arguably even other industries, too. A throng of titans control the lion’s share and dominate both the market and a space in everybody’s mind. If this article veered a little too far off the rails for your liking, just remember what I said at the start: this is a little more than just an experiment I made when reconnecting to the mainstream. It’s also a snapshot of how I see the world right now. Aaron der Schaedel spent his 31st birthday writing this article; which would also have been Gary Gygax’s 81st, were he still with us. Sharing Gary Gygax’s birthday has granted Aaron no special powers or abilities, and he is still, in fact, really salty about that. You can tell him to get over himself via Twitter. You can also check out his YouTube Channel, which is his own attempt to slay the metaphorical dragon. Picture Reference: https://www.facebook.com/pg/kentokyocon/posts/ We’ve been in the middle of an RPG renaissance for several years now. More games are coming out than ever before, and we’ve had huge inrushes of players eager to snap them up. And while creative changes in the industry, positive outreach from the community, and the ascension of geek culture have all played their part, something we can’t ignore is the popularity of YouTube campaigns like Critical Role or Acquisitions Inc. These games have allowed audiences who have never seen an RPG in action before to watch how it’s done by the pros, allowing them to get an idea of how all these moving parts should look when you flip the switch. In broad terms, we can all agree that’s a good thing. Especially for players and dungeon masters who want to get into the hobby (or into a particular game), but who lack more experienced people to reach out to, and could use some examples of how things work. In specific terms, though, there has been a definite up-tick in complaints that a particular game isn’t run like what they see on the Internet. So if you’re a player or dungeon master worried about how your game doesn’t look like the sort of game Matt Mercer would put together, take a deep breath, and relax. That’s okay. In fact, it’s great. Here are some reasons why. Reason #1) This Isn’t Your Job Most people out there who love RPGs play them for fun. What a lot of folks forget is that, for the YouTube dungeon masters and convention games that people buy tickets to watch, that’s not the case. They are doing this to entertain you, the viewers. Is it fun for them? Yeah, probably. But their main concern is more about what gets more viewers. Hence the celebrity guest players, the carefully crafted story lines, making sure a lot of stuff is worked out in advance for rules calls, etc. If you’re running your game for the purpose of drawing ears to a podcast, or getting a lot of hits on YouTube, then by all means mimic what the successful games are doing. But if this is for funsies, remember that you don’t have to put on the whole three-ring show the way the pros do. Reason #2) Professional Games Aren’t Cheap You see all the props, the cool minis, the fully laid-out map, etc. that are on these shows? Well, they’re there in order to give the audience something cool to look at. Because the advent of popular 3D printing may have made such things cheaper, it has in no way made running a game that looks that good cheap. So if you’re not working with a big budget, there is zero shame in using re-purposed green soldiers, monster figures from SCS, or just Lego figures, and drawing with dry-erase markers on the map. This same logic applies to all the complaints you might see regarding production values. From the ambiance of the set, to any music used, or just to how much in-depth RP the players and dungeon master do. Remember that these things have costs in terms of time, energy, preparation, and setup. If you don’t have the budget for bells and whistles, don’t worry. Engage with the game, and the story you’re all telling. Reason #3) Every DM Is Different While he catches a lot of flak, Matt Mercer himself has said that every DM should be free to develop their own style, and to find what makes their game work for them and their table. RPGs aren’t like organized sports, where if you want to be the best you should imitate those who are most successful (which, in this case, means the people who are known professionally for running entertaining gaming sessions). Are there things you can learn from the folks who captain these YouTube campaigns? Of course there are! But there’s a big difference between learning a lesson or taking a bit of flair to work into your own routine, and outright copying what they’ve done. So remember, there are no rules when it comes to this hobby. And if the only objection someone has is, “That’s not how they do it on TV,” then you should politely inform them that they and their character are not a part of that particular show. Reason #4) Are You Not Entertained? Have you ever had a discussion with someone who tried to game shame you? This happens more with video games where people will talk down to you if you prefer a game that is older, doesn’t have good graphics, or isn’t the current in thing to play, and it’s just as asinine in those situations as it is with tabletop games. Don’t compare yourself to others, especially in a story-based, creative endeavor. It doesn’t matter if your sword-and-sorcery campaign doesn’t feel like a Robert E. Howard adventure, and it’s immaterial if your horror game leaves out the earmarks of Lovecraft’s finest work. And it’s no more important that your game looks or feels like a professional podcast, as long as everyone is enjoying themselves playing it. Reason #5) You Have Different Needs Not to get repetitive, but these popular games exist to entertain an audience. That is the driving goal behind a lot of the decisions that get made (one in particular that comes to mind is Critical Role switching from Pathfinder to Dungeons and Dragons 5th Edition in order to speed up play so the audience wouldn’t get bored). However, you and your players may have needs or wants that this kind of format simply cannot provide for. As an example, if you want that kind of mechanical complexity (or you feel that rules which have been truncated or re-written to speed up the game on-camera should be run differently), then it’s okay for you to play games that scratch that itch. If you want to deal with the kind of subject matter that wouldn’t show up on these shows, or if you want to do deep dives into game setups that might not seem as interesting to a broader audience, you can do that as well. Games on YouTube are about what makes the audience happy. Your game is about your and your group’s needs, and unless you’re broadcasting, focus on what you need out of the game in order for you to enjoy it. For more from Neal Litherland, check out his Gamers archive, as well as his blog Improved Initiative! And if you’re looking for a new YouTube channel dedicated to gaming, stop by Dungeon Keeper Radio. Picture Reference: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/78320481003470118/ If you’ve ever been part of a long-running game, you’re no doubt familiar with what some folks call supplement fatigue. This is a condition that happens when the game you’re playing has a great deal of additional books beyond the core, and you start to feel overwhelmed trying to take it all in. Even if you’ve been with that game since the very beginning, constantly reading new books and trying to keep your mental software updated feels exhausting. This is around the time people start talking about “bloat” in regards to a game. Because it used to be streamlined, easy-to-play, and no problem to run. But now… well, now it takes an entire library shelf just to make one character. If you’re one of those players (or storytellers) who gets bent out of shape over a game being “bloated” then you’ll be glad to know this problem doesn’t really exist. It’s all in your head. I talked about this back in There’s No Such Thing As Bloat in RPGs, and Here’s Why, but some of these points need to be reiterated. Points like... 1) One Player’s Feature is Another Player’s Flaw Think of the mechanic you hate most in a game. Maybe it’s your least favorite race, that vampire clan you can’t stand, or that one rule that you just wish would be deleted. I guarantee you that, for another player, that is one of the things they love about the game. If you’re honest with yourself, I bet there are at least a few supplements that you think are good, or which represented a step in the right direction for the game as a whole. But those supplements you like will be seen as unnecessary bloat by other players. So if we can’t even agree on a definition about what bloat really is, then chances are it may not actually exist at all. 2) Finding Things Isn’t Nearly As Hard As You May Pretend It Is Another metric some people use for accusing a game of being bloated is that it becomes impossible to find the rules you need in a timely fashion. You can’t remember if this merit was in a clan book, or in that one Middle Ages sourcebook, or if it was somewhere in the base book’s optional rules section, and everyone’s looking at you, waiting for a ruling, or for you to declare your action. In ye olden days, this could be a legitimate problem, requiring several folks at the table to have an encyclopedic knowledge of the game’s rules and errata. However, technology has shouldered a lot of this workload for us. Now all you need to do is type in the name of a mechanic, or ask a database for the rule, and pop you’re there in seconds, and you can read the text aloud for your table. So while there is more stuff, it isn’t as difficult to parse through as a lot of folks would have you believe. 3) You Don’t Have To Use It While there might be some crazed completists out there, it’s important to remember that supplement books are just that… supplements. If you want to include the half-dozen Ultimate books in your Pathfinder game, or all the special rules and lore in the different clan books for your Vampire campaign, you totally can. That’s what they’re written for, after all. But you are under no obligation to do that. I’ll repeat that, because it bears repeating. You do not have to buy supplementary books, you don’t have to read them, and if someone at your table actually has one, you’re under no obligation to allow them to use that book in your game. If you just want to stick to the basic books with no additions, that’s your call. If you want to allow the first two or three supplements, but nothing else, that’s cool too. And if you want to allow anything and everything at your table, that’s your choice. It’s all there for you to pick what you want from. And it seems like a lot of folks forget that. But Game Publishers Just Want My Money! I’m going to say this for all the folks in the back: Every business out there that creates a product you want is out for your money. The authors you read? Money. The video games you buy? Money. Your favorite YouTubers? Well, they’re trying the best they can to get money. These companies don’t put these products out just for the love of the game (most of the time, anyway); they’ve got bills to pay. And if there’s a market of folks who want more content for a game, then rest assured publishers are going to keep putting out more stuff as long as people keep buying it. That’s why we’ve got something like 500 The Fast and The Furious films. And just like with gaming supplements, you don’t have to go see them if you don’t want to. Nor are you required to like everything in a series if you’re just a fan of one or two extra installments. Keep what you like, and ignore the rest if it makes your games better for you. For more from Neal F. Litherland, check out his Gamers page, as well as his blog Improved Initiative! You can also find books like the sword and sorcery novel Crier’s Knife on his Amazon Author Page. Picture Reference: https://www.etsy.com/au/listing/183531915/rifts-conversion-book-rpg-vintageantique There has been a lot of complaining about the Pathfinder playtest, and believe me, I’ve done my share of it. And though I summed up what I felt was wrong with the game as a game back in October with My Final Thoughts on The Pathfinder 2nd Edition Playtest, I’d like to talk about something tangential that I feel hasn’t been covered as much in the debate of whether or not the playtest is or is not a good game. Because I’ll admit that it’s functional, even if I feel it’s held together with duct tape and string in a couple of places. However, what it is not is Pathfinder as we know it. That isn’t just grognard-speak for, “This new version of the game isn’t the one I learned, so therefore it’s ruined!” either. Because Pathfinder wasn’t just another fantasy RPG in a market where you can hit one of those by chucking a rock. It was a game with a very distinct identity, as well as a unique heritage that allowed it to fill a particular niche. It had a brand, and the people who played it (or who asked about it) understood what made it different from the competition. This new version we’ve seen and played, though, doesn’t carry through any of that uniqueness, and it feels like it’s trying to ride the brand name without offering any of the things that players associate with the brand. For example… 1) Copying What’s Popular (Instead of Being The Unique Stand-Out) When Pathfinder first claimed its market share, it did so by lifting the falling light of the DND 3.5 engine. There were other games using it, sure, but Paizo took that engine and made it bigger, faster, louder, and stronger. They carved out their own niche, and when the 4th Edition of DND under-performed, Pathfinder existed as a viable alternative that was mechanically different from 4th Edition in a lot of meaningful ways. This new playtest, though, feels like it’s trying to play catch-up rather than stand-out. While it’s true that it isn’t exactly the same as Dungeons and Dragons 5th Edition, you can see whose homework Paizo was copying with this playtest. And while 5th Edition is a stand-out in the marketplace, it’s on the other end of the kind of play that Pathfinder tends to be associated with. So it feels like Paizo is just trying to be more like the latest success story, which isn’t working because that game already exists, and this attempt to hybridize it is just not going to appeal to players who like Classic Pathfinder or players who like 5th Edition. 2) Limiting Mechanical Freedom One of the biggest selling points Pathfinder has, in my view, is the sheer amount of mechanical freedom it offers. If you have a character concept, there is probably some way you can make it happen using the rules and options as they exist. And you aren’t just re-skinning an existing mechanic so that it looks different; you have the specific mechanics you need to manifest your idea. My best example for this is playing someone descended from storm giants. In 5th Edition, for example, there is nothing that stops you from making this claim. You can use it to justify a maxed-out strength score, and describe your character as blocky and gray-skinned. If you’re playing Pathfinder, though, you can take a feat that states explicitly that you are a storm giant for all effects related to race. And if you take a second feat, you are now immune to any effects of electricity damage. It’s more than story justification; according to the physics of the world, you have storm giant heritage. There are dozens of examples in Pathfinder Classic of this kind of mechanical freedom. You want to play a character that’s half-orc and half-elf? Cool, take this racial option and this feat. You now have a half-elf with a bite attack and tattoos, or a half-orc that can do tricks with a bow usually reserved only for elves. You want to play a Jekyll and Hyde character who literally transforms into someone else? There’s a prestige class for that. You want to be a celestial being raised on another plane who is coming to the material world as a foreigner? There’s options for that, too! The playtest, though, is all about rigidity of path and tamping down on your mechanical freedom as a player. Multiclassing is discouraged to the point that it feels token, all classes are forced to make choices that narrowly define their abilities and progression, and the new feat system has all the complexity of the old one without any of the mix-and-match ability you had to make exactly the character you want to play. One of Pathfinder’s greatest strengths as an RPG was the flexibility of its mechanics, and how you could blend them to form exactly the concept you wanted without having to bend any of the rules as they were presented. In this playtest you’re stuck with archetypes whose abilities are rigidly defined, and which gives you almost no options to meaningfully deviate from the path that’s been laid before you. 3) Pointless Complication Pathfinder was always the crunchier fantasy game on the market. If you like a game that had rules for what penalties you deal with when you’re drunk, to exactly what saves you need to make to avoid drug addiction, then Pathfinder was your jam. However, even if you found some of the rules cumbersome or unnecessary, you could at least envision situations where they would be useful. The playtest kept all the complexity, but distanced it from scenarios where it helped rather than hindered. The best example of this is the bulk system. In Pathfinder Classic (and most games with encumbrance rules) you simply look at your Strength score, and that tells you your light, medium, and heavy loads, as well as your maximum amount of ability to lift, push, etc. The playtest uses a bulk system, which means you have to look up an individual item, determine what its bulk value is, and then run your attribute through a formula to figure out how much bulk you can carry. You might argue that they were just trying to do something different, but any playtester would have told you immediately it was a bad idea. It overcomplicates a simple mechanic that most players would like to ignore in the first place, so why would you do that? You see it all over the place in the playtest. If you want to make a combat maneuver like a disarm check or a grapple (things that, previously, any character could just try to do), now you need to make a specific skill check. Not only that, but if you’re not trained in that skill, then you may not even be able to attempt the thing you’re trying to do. It’s the same line of thought that staggers out your racial abilities over a dozen levels, because it makes complete sense for a half-orc to get darkvision only once they’ve killed enough monsters to activate the eyes they were born with. Pathfinder players aren’t scared of a complicated game. But they’re used to the complications at least making sense, and too much of this game seems to have been complicated for no other reason than to make it crunchier even if those changes added nothing to the experience but irritation. For more gaming thoughts from Neal Litherland, check out his Gamers archive, his blog Improved Initiative. To read his fiction, drop by his Amazon Author Page! Picture Reference: https://paizo.com/pathfinderplaytest My earliest RPG experiences were with D&D 3.5e, 4e, and Pathfinder. These games are known for being “crunchy” (having many complex game mechanics), and 3.5e in particular was known for having a glut of supplemental materials of dubious quality. With these games, because of the breadth and depth of mechanics and the focus on tactical combat, supplemental materials often negatively impacted game balance, and that had a chilling effect on my perception towards homebrew or 3rd-party published content (materials not produced by Wizards of the Coast). Over the years I’ve moved away from those kinds of games, and towards more rules-light games like FATE, Cypher, and OSR (D&D 2e or earlier, or modern games built with a similar design philosophy or shared mechanics). One thing that I’ve found so refreshing and rewarding about these systems is how easy it is to modify the games to suit your needs, without having to worry too much about negatively impacting game balance. With some consideration, these modifications could even work for a medium-crunch game like D&D 5e. Here are 3 ways to modify games. Treat these as ways to think more about why the mechanics of a game exist, and how changing them affects game balance and the play experience, so that you can come up with your own modifications! 1) Power Points Here I’m using power points to refer to any kind of system where players gain points for their actions, which can later be spent to affect future actions. These are often employed in “narrative” games, as with the fate points in FATE, to encourage players to roleplay and to interact with the world in a way that drives the plot forward. However, I think this system can be used for several other purposes, such as to fill “holes” in character builds, to bring a little cinematic flare to medium crunch tactical combat games, or even evoke unique themes. I ran a campaign in my Phantasmos campaign setting using Numenera as the game system. The Phantasmos setting has various species and classes of its own, not all of which mapped cleanly to the options available in Numenera RAW (rules as written). Let’s use Arpaia the dogu apoptomancer as an example. Dogu are a species with several unique abilities such as shifting between a humanoid and monstrous form, and a sense of hyper-touch, and apoptomancers are a character class focused on the manipulation of controlled cell-death and the neuro-immune system to induce metamorphoses. Rather than constricting the player to a limited set of descriptors (like species) and foci (like feats) that reflect all of these varying and specific abilities, we had him train in the skills “dogu senses” and “apoptomancy,” which he could use to do things that his character should be able to do, but aren’t strictly built into his RAW character sheet. Importantly, if he were to use these skills in any way on a scale of power or utility comparable to his actual RAW special abilities, he would have to spend power points. Not only does this give him greater flexibility in character building and ensures that he can always do the things he should realistically be able to do, this encourages creative thinking and interactivity with the story to get power points and leverage his abilities. A final note on power points: The game Tenra Bansho Zero has a really cool karma system, which is used both for character building and as power points. However, in that game, as you acquire more karma, you become increasingly likely to turn into an ashura, a demon. The point of the game is in-line with the Buddhist philosophy of separating oneself from material attachment (as expressed by resolving karma). The strengths and weaknesses of material attachment, the Buddhist themes of the setting, are actually instantiated within the game mechanics using power points! 2) Change The Dice So this gets into probability theory, which really should be a whole post in its own right, but I’ll go over some basics here. While many games use a d20 for action resolution as a matter of convention, I think most good games are mindful of their dice. A d20 is a very different beast than a 3d6 or FATE dice system, and understanding these differences can radically change how a game “feels.” Note that I will not be discussing games which use dice pools here, as the probabilities get a bit more complex, and I think that would be better suited for its own post. A d20 is a uniform distribution, meaning there is an equal probability of rolling any value, which from a range of 1 to 20 means 5%. The wide range and uniform distribution are why people often describe d20 as being “swingy,” meaning it is common to roll excessively high or low. A 3d6 is a normal distribution, or bell curve, meaning that you are most likely to roll the mean, and the further from the mean a given value is, the less likely you are to roll that value. With a range from 3 (rolling [1,1,1]) to 18 (rolling [6,6,6]), 25% of the time you will roll a 10 or 11 (27 ways each to roll a 10 or 11) , whereas you will only roll a 3 or 18 <0.5% of the time each (because, as already stated, there is only one way to roll a 3 or an 18). This is why 3d6 is less swingy; most of the time you will roll somewhere near the middle of the distribution. So despite the fact that these dice mechanics have very similar ranges, they have very different probabilities. I’ve already explained how this affects swinginess, but it also affects the impact of modifiers. Unlike a swingy d20, with 3d6, assuming a difficulty of 10 or 11, you’re more likely to narrowly miss or succeed, so the impact of a small modifier is greater. For example, normally you would have a 62.5% probability of rolling a 10 or greater. However, with a modifier of +1, the range is now 4 to 19, but the dice remain the same, so essentially you’re sliding the distribution up by 1. In other words, because a roll of 9 now gives you a value of 10 (roll+1), and there’s an 11.6% probability of rolling a 9, you can add that to the 62.5% for a 74.1% probability of rolling 10 or greater. With a d20, that +1 only nets you an increase of 5%! That being said, for d20, no matter how many modifiers you have, each nets you +5% towards a higher value, whereas with 3d6, because the probability of a given roll gets lower the further you go from the mean, higher modifiers give you diminishing returns. It may help to think about weapons. In Dungeons & Dragons, a greataxe has a damage roll of 1d12, a uniform distribution comparable to a d20. Greatswords have 2d6 damage dice, a normal distribution. They average about the same; minor quibbles aside they are roughly equal in power, but they behave differently, and in a way that reflects a specific intention. Compared to the greataxe, the greatsword will be more reliable, it will generally deal about 6 damage, only occasionally doing exceptionally more or less. The greataxe will average about the same, but will swing wildly from very little damage, to very high damage. Keep in mind that these dice distributions also affect character progression and relative power. In a game where dice modifiers improve over time (such as by leveling up), there will be a much larger difference between lower level characters in a 3d6 system than a d20 system, but a much larger difference between higher level characters in a d20 system than a 3d6 system. All of this is to say that dice matter! There is so much more I could say about probabilities, but as a last aside, keep in mind that the range of values on a die also matter. For instance, for FATE dice, you roll 4 dice, each with two negatives, two neutrals, and two positives, meaning you have a normal distribution centered at 0. Because the range extends into the negatives, is a relatively narrow range of -4 to 4, and is centered at 0, the impact of a modifier will in general be much larger than a 3d6 system, where the range is much larger and entirely positive. All of this is to say, if you understand how these distributions affect your game, you can substitute them safely. If you want to play D&D 5e where the game is less swingy, and where characters become significantly more powerful from level-to-level at lower levels, but there is less of a power curve at higher levels, just substitute your d20 for 3d6! 3) Combat Modifiers Obviously not every game is about combat, or treats combat to varying degrees of abstraction, but even so, many games deal with combat, and often not well. Personally, I’ve always felt like coming up with tactical character builds in crunchier games is fun, and the idea of combat is fun, but in practice it often gets bogged down. Either the game is so crunchy that it’s slow and cumbersome, or the game is so light that it becomes rote and stale. However, there are some simple ways to make combat faster or more fun, without fundamentally altering the game! The easiest thing is to abstract. As the GM, try to apply narrative flourishes to the enemies’ actions. Describe how they attack, how they defend, how they behave in response to the players (even if it’s just a matter of taunts or sneers or wide-eyed looks of apprehension). Encourage the players to do likewise. Regardless of what spell/ability/move they do, let them have fun with how they describe the flavor of that action. A “missed” attack is much more satisfying when it’s described as a sure strike that was deftly parried, or glinted off the enemy’s armor. This can be difficult to do at first, but the more you practice, the more natural it will become. In terms of mechanics, one option is an escalation die. One way to implement the escalation die would be to have a d6 appear at the beginning of the second round facing 1, and increase the number each round, up to 6. All combatants gain the value of the escalation die to their attack bonus, so that as combat progresses, all combatants are more likely to hit, making the game deadlier. This creates tension, it makes weaker enemies potentially more dangerous if in large enough numbers, and it moves combat along quickly and in a satisfying way. This kind of modifier could be applied as a random roll instead, reflecting the randomness and deadliness of real combat, or could be set to a specific value as a way to signify the stakes of a given encounter. An alternative way to do an encounter die would be to have the die lower AC, increase the damage roll rather than the attack roll, or give the defender a counter-attack chance (x or lower on a d6 allows counter-attack / attack of opportunity, where x is the value of the escalation die), or activate special abilities from the enemy or evoke some other “event”, such as more enemies arriving or a change in the environment. In addition to affecting the flow of combat, these alternative options can also have fun narrative implications. Manipulating quantities of enemies and action economy is another useful combat modification, especially for mass combat or “boss fights.” Hordes of weaker enemies may seem cool at first, but either they’re too weak, in which case they’re ineffectual and their turns are a boring waste of time, or they’re just powerful enough that through sheer number of actions they can overwhelm the players in a way that is also unsatisfying. Instead, by clumping these weaker enemies into a smaller number of more powerful swarms, the encounter can be faster and more engaging. Even quicker, one could make the entire swarm a single entity with multiple actions. Likewise, rather than defaulting to giving a “boss” enemy a swarm of underlings to balance the action economy, an especially big-bad could get multiple actions per turn, or for a literally big-bad like a kaiju, its body parts could be treated as separate entities. These are all intentionally loose and system-neutral, to show how you can go about thinking of any game. Crunchier games will be harder to modify without accidentally creating imbalances or “breaking” the game in other ways, but even those games can be modified if you carefully consider what affects the modifications will have. Modifications can affect how a player perceives an encounter, how they build their characters, the balance of the game, and the flow of combat, and any number of other things. If you understand the game and understand what you and your players want, then you don’t have to be afraid of modifications! Max Cantor is a former cognitive neuroscientist and soon to be data engineer, whose love of all things science fiction, fantasy, and weird has inspired him to build worlds. He writes a blog called Weird & Wonderful Worlds and hopes people will use or be inspired by his ideas! Picture Reference: https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/MadScientist This is a slightly updated version of the article that appears in my Nuggets #1 zine. I've been creating a new world seven hexagonal spaces at a time. Here is the beginning of that; an area for your player character to explore around a small village. It is written system agnostic and is easily adapted to any edition of old school role playing games. The village, Victoria's Tower, was built around and is named after a the wizard's tower at its center. There was an accident and the sun is frozen at dusk for 20 more days (totalling a month). The village and its surrounding hexes are stuck out of time. Anyone can travel back and forth, but no time passes naturally until the end of the month. Spells and other magical effects work normally. 1) Plains And Village A mage, Victoria, lives in a tower and a village has evolved up around it. Victoria built here because of the magic contained in the burial mounds from a long dead civilization. The village provides reagents from the sea in exchange for protection from the wizard. Victoria has frozen herself and cannot fix this. Her tower is protected with glyphs of warding and arcane locks. There are about 20 small crates filled with enchanted fish (see 12) here waiting for Victoria to open her door. 2) Plains And Farms Mostly farms and the location of the ancient burial mounds, these plains feed the village. There is an underground tunnel connecting the mounds to Victoria’s tower. If the twelve mounds are explored, four are connected to the tower and found emptied, four more are silent, and the last four are haunted by undead. One contains a flail, Beast Render, that smells of patchouli and deals +2 damage to beasts. 3) Plains And Lakeshore A body of water where fishermen catch gillies and stuff them into enchanted scarecrows on the shore. After four days the fish are removed and delivered to the wizard. There is also an island where reagents and medicinal herbs are grown. Barren mothers (unknowingly cause by Victoria’s experimentation with ancient magics) come here with their husbands to tend the area while the men fish. 4) South Tower Hills A well traveled road has signs of a fight and two dead worgs killed by a piercing weapon. There is a woman nursing her wounds under a small rocky overhang away from the road. Lune, an elven warrior, is armed with 2 short swords. She stands her ground if threatened, but seeks to be left alone. She is bringing the remains of two humans to add to the scarecrows in area 3. Once a month the scarecrows need to be refilled with fresh kills. Only Lune and Victoria know of this dark deed. Lune will not let players know about this unless her life depends on it. She will say that the remains she carries are from her family and she is making a pilgrimage to the lake to bury them at sea. 5) Moonlit Hills These tree barren hills hide a duchess, Lady Em Winter-Borough, waiting under the moonlight for a clandestine meeting with one of the clerics, she is dying and has a book of secrets to trade for a cure. The players will not recognize Lady Em, as she is from a kingdom far away. She claims to be Dass Whitehall, a noble from a nearby kingdom and is waiting for her slower coach, with her luggage, to catch up. Her coach is hidden here and can be found if players search the hex. If the players search within the coach they can find a diary and a contract that reveals Lady Em’s true identity and the fact that she is dying. Her family made a pact with a devil that has cursed her with disease. She is looking to find a cure or a loophole in the contract. 6) Ogre Hills An ogre, Rockgrinder, make his home here in an out of the way cave that players can find if they search this hex well. He hides if seen and has promised a raven (actually Victoria) to keep the town safe. Rockgrinder has a ring that lets him talk to animals and uses them for information. In addition to hunting predators, the raven leads him to food, but has been absent for over a week. 7) Plains Of Dissonance The wizard’s apprentice stays with a group of traveling men. These are clerics of an uncaring god and they seek to destroy the wizard because she is tampering with ancient magics. The clerics have no names. The apprentice can locate all the wards in the wizard’s tower and is being charmed by the clerics to give them the information. The apprentice has not entered the tower in eleven days for fear of accidentally setting the wards off. Richard Fraser has been roleplaying since the early days of Dungeons and Dragons and started with the red box in the eighties. He currently prefers to DM fifth edition D&D, though reads a lot of OSR and PbtA. He currently has podcast, Cockatrice Nuggets and maintains a blog, both of which can be found at www.slackernerds.com.