|

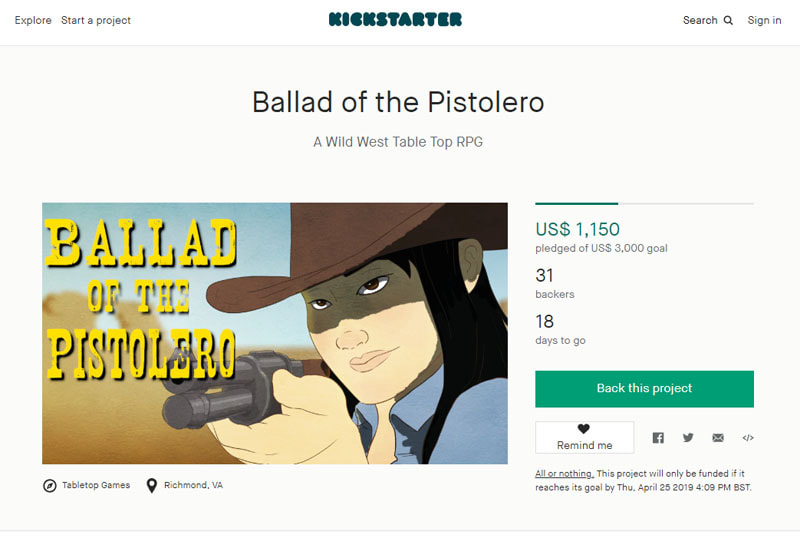

In my time as a GM, I often use classic storytelling tropes. The 3 act structure is heavily referenced in many tips on running a good game. So can similar guides help create a good character? So I wanted to look at the first several key points of the hero’s journey in order to see what points should be included in our characters. I’ll be asking and answering whether the first steps should be included and if so what they add to a character. For reference, there are a couple of different versions of the Monomyth/Hero’s Journey; I’ll be using the one from The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell. 1) The Call To Adventure The call to an adventurer's life is a pretty basic tenant of character creation. What called a character to the life they currently live? GMs talk about a call to adventure in their game that will cause the characters to come together, but most Lv 0 characters in RPG’s don’t resemble the very beginnings of that character’s arc. All of our characters come with the beginnings of their skills or the inclination towards them. So what caused our characters to become the adventurers they are today? In character creation, it is important to create a major goal for the character - a lifelong quest that the GM can interact with. However, it’s important that the goal pervades the overall arc but is still involved in smaller complete adventures. Thus the call to adventure implemented into character creation can have powerful story impact, perhaps even too powerful if not thought through. 2) Refusal Of The Call Should our characters refuse the call to adventure? Refusing the call to adventure is where the danger of accepting their new task comes into focus. For some of our characters that risk is death by unknown monsters and for some it’s public shame; there are prices to our characters failings. A character also in this case usually establishes what fears and weaknesses might hold them back on the upcoming journey of the campaign. So this very well could be a good time in your backstory to establish important disadvantages your character starts the campaign with and maybe mention why they have them. Ultimately, refusing the call to adventure humanizes the character. So, if you constantly find yourself in the murder hobo camp and want to get out, including the refusal into your backstory could be an effective way to fight that. Give your character weakness and let it make them weak. So should your character refuse the call? Not necessarily. But, I think it is important that you give them a reason to and include that into the game. 3) Meeting The Mentor Each of our characters has an extraordinary set of skills and the way they acquire those skills is a big point of how they form as adventurers. The hero’s journey assumes that it is some kind of wise old man teaching the hero the way. Campbell claims that the mentor, in addition to acting as instructor, represents “the benign, protecting power of destiny.” The meeting of the mentor represents the assurance of the validity of a character’s personal quest and the ultimate success of it. This mentor can be a very powerful tool when your GM is crafting a story with your characters. So I would suggest taking time to consider how a mentor’s specific influence makes your character’s skill set and quest different from others with the same training. 4) Crossing The Threshold Here the hero leaves the world he is comfortable with. This crossing allows the character to leave their life and become part of the campaign. Whether a physical or metaphorical barrier there does need to be a finality to the change in our character’s life. At this point, it is important that the character has both the reason to leave their comfort zones and something forcing them to do so. This is the point where the character’s backstory becomes just that: a backstory, motivations derived from the past. This should be a defining moment for the character that frees them of the immediacy of past obligations and allows them to take up the life they lead in our campaigns. Think of Frodo or Luke Skywalker. Frodo leaves with ties to the shire but no true obligations. He carries friends with him and a mission with him but none of his life from the shire is key to any of it. In the case of Skywalker the person literally asking him to stay for his home responsibilities, his uncle, literally passes away. Making our own characters in a wider story is always a challenge for tabletop roleplaying games. It’s important to make sure that our character gives more opportunities for unique character moments. For this, I think models like the Hero’s Journey give a good way to ensure our character’s story is rich enough to be worth interacting with however integrating it into a larger story with other characters and NPC’s is the challenge of the players over an author. My best advice is to make sure that your character has a rich past that is in the past. Adventurers should be ready to start their life over and experience change. Of course, this varies by system, player, and playgroup. As a GM I typically use the 3 act structure but realize that I may need to abandon some planned things to give the players the best experience. So as a player I think we should follow a structure like the Hero’s Journey but realize rarely does that kind of planning actually fully make it to the table. Bo Quel is a Legend of the Five Rings Fanatic From Virginia. He plays and GMs several systems where he focuses on telling enriching stories and making characters that are memorable. He also is the GM/Host of Secondhand Strife, an L5R RPG actual Play Podcast. Image Credit: What makes a hero? - Matthew Winkler Ted talk https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hhk4N9A0oCA Sometimes friends drift apart, or disagreements can dismantle a party. What do you do when you need to find a new group to game with? Though currently difficult due to COVID-19, we've got your back on how you can saddle up and find your new party. 1) Conventions Once convention season opens up again after the pandemic is over - conventions are a great way to meet scores of new people in a short amount of time. While not everyone can afford the expense of attending one of the mega conventions like San Diego ComiCon, the benefit to gaming becoming more mainstream and popular means there are many more small local conventions than ever before! There are often conventions that are purely just about gaming, or even specific types of gaming. The drawback to seeking a new gaming group even at a small local convention is that they might not be local. But the odds are in your favor by sheer numbers and opportunities with different gaming sessions and panels. Even if you don’t find your new gaming group, you can still have a great time playing some fun games with other con goers and potentially make some new friends. 2) Local Game Nights A better way to increase your odds of encountering local gamers is, after the pandemic, to hit up a local game night at a game store or venue that supports game nights (such as an arcade bar or a family run restaurant). Most game stores have different game nights that are themed to specific days and usually have a freeform game night at least one night per week. This offers the opportunity to find new group members for a particular game you want to play, or to join an existing group that you mesh with. It also takes the guesswork out of choosing a location for your new group’s game nights, since you’re already meeting at a hosting venue. If you don’t find a new game group on the first try, don’t be afraid to try again. While most themed game nights will have the “usual crowd” there may be new gamers that stop by looking for a group just like you. 3) Join A Facebook Group Scouting new local groups can be tough, and exploring new game shops and game night locales can be intimidating. A great way to find new gaming group members without the social pressure is by searching groups on Facebook. The social media platform has dozens of groups specifically tailored to different games. It’s also a great way to get a feel for the other players in a group via the discussions on the Facebook group pages. It will become clear which groups and gamers are more “hardcore” and which are more “casual” by the types of discussions in the groups. Reading them ahead of time takes the social pressure off so you “know” what kind of gamers you’ll be sitting down to play with. You never know who you might connect with and what local fellow gamers you might find. 4) Search On A Gaming Forum This can be a bit more intimidating than joining a Facebook group. Gamers that frequent forums are typically more “hardcore” about the games they play than the casual gamers that are more likely to frequent open Facebook groups. If you consider yourself a hardcore gamer, or are up to the challenge, this may be a great way to find an experienced group to play with. There are always clusters of gamers looking to join new groups, and technology can help bridge the distance if local gaming isn’t possible. Utilizing video chat like Skype or Zoom with digital gaming programs like Roll20 can make game night happen no matter where your group members live. 5) Start Your Own Group This option may be the most intimidating, but it can sometimes be the “best” option. Create your own Facebook Group, or post on a gaming forum that you’re looking to build your own gaming group. Let the world know what kind of group you’re looking to play with, and what you bring to the table. Do you have a venue? Books, maps, figurines? Or maybe you make the best game night snacks? Whatever makes you a key player for your new game group, shout it loud and proud and see what other gamers you might reel in. Seeking a new game night group is always a challenge, regardless if it’s your first game group, or you’re a seasoned player. Take a chance on these tips and don’t give up! Your best game night group is out there waiting for you. Alice Liddell is an author, artist, and performer who loves bringing magic and fantasy to all aspects of her working and personal life. Whether it’s DnD with friends, or a round of Fable solo, Alice has always loved gaming of all kinds. You can find her work on her social media handles Facebook, or under littlalice06 on IG and Twitter. Picture Reference: https://www.wallpaperflare.com/play-board-game-cube-human-don-t-be-angry-game-board-figures-wallpaper-ajphf/download/4096x2304 Since the boom of the tabletop roleplaying industry and kickstarter, we have been able to enjoy games from all over the world from a diverse amount of people. Unsurprisingly, the country with the most horrific creatures on the planet is producing some of the best tabletop RPGs. Due to distance, a lot of these amazing games aren't being showcased in America. So let's change that! Here are some of the best games being produced by Australian designers right now. 1) Relics: A Game of Angels The first stop on our road trip through Australia is Steve Darlington, creator of Relics and owner of Tin Star Games. You may have heard of Stever Dee, his moniker, as he has been part of the creation of Shadow of the Demon Lord and Vampire:The Requiem. Now his work is focused on a new creation! Relics: A Game of Angels is a game where you play (surprise!) angels who have come to earth to wage war against demons without the use of divine powers. The war has raged for centuries with no side gaining ground. The catalyst for this game is the withdrawing of God from the cosmic spotlight and vanishing from our perceived existence. What do these thousand year old angels do now that they no longer have guidance, a deity to fight for, or someone watching their back? These are some of the questions you will struggle with as you explore the world of Relics. It uses the tarot-based Fugue system originally created by James Wallis. Not only do the cards tell you about what happens, but also the card helps guide the scenario by the cues from the card’s meaning. If you are interested in a game where you can play ancient beings who played a part in creation, look no further. Furthermore, I cannot stress how amazing and helpful the Fugue system with the tarot deck is with pushing the story forward. The tarot deck offers so much storytelling inspiration for each action. Join the fight as you learn your place in this vast universe and make sure to pick up a copy of Relics. 2) Good Society: Jane Austen RPG Next on our trip through Australia are the wonderful designers from Storybrewers. Vee Hendro and Hayley Gordon have brought to life the vivid and romantic stories of Jane Austen through their game Good Society, which won Best Rules by The Indie Game Development Network in 2019. In Good Society, you adopt the personas of your favorite character types from Jane Austen novels and movies. You can be a wealthy debutante, a poor poet seeking love, write to your friends and family concerning the local gossip, or uncover scandal as you dance under crystal chandeliers. Whatever flights of fancy catch your eye within the pages of an Austen novel, you will find them in Good Society. The game uses cycles of play where you create scenes with other players, send letters, create rumors, and monologue. The conflict resolution is different than what the typical D&D player may be used to and uses a consent based token exchange. At the start of a cycle of play you have two tokens that allow you to to affect another character or accomplish an unlikely task. It is always a conversation; If you want to spread rumors of another player’s substance addiction, you must first enter negotiation with the other player. Everything is consent based and allows for a wonderful “yes and” and “yes but” style of play. Good Society was successfully funded via Kickstarter and a new expansion is coming out later this year. If you are looking for a narrative focused game with mechanics that do not get in the way, look no further than Good Society: A Jane Austen RPG. 3) Fragged Empire Our final destination brings us to Fragged Empire by Wade Dyer of Design Ministries. Fragged Empire is a post apocalyptic sci-fi game where you play one of the genetic creations of humanity. After a genocidal war, all the remaining species are trying to reclaim the society they once had. The base game has 4 non-human species that you can play, each one with its own special genetic purpose for their creation. The Corp, a species created in Humanity's image, were rejected by their creator and have now found their niche in controlling trade and finance. The Legion was a species created as soldiers for the war; now that the war is over, their species desperately tries to encourage their people to raise families and start farming. The mechanics are easy to understand yet provide a lot of tactical nuances that create exciting combat. You can control combat drones, perform multiple combat actions in one turn, and pilot space ships in epic space battles. The conflict resolution mechanics is a skill based system where you roll three six sided dice and add in your relevant skill bonus. If you describe the scene with a level of intensity and flair as the scene demands, the gamemaster can also award you a bonus. It doesn’t end there though. If you roll a six, you unlock a Strong Hit which allows you to perform special feats such as rerolling a d6. Character creation provides a diverse plethora of options in and out of combat, including unique Strong Hit abilities. There is so much flexibility and customization in the game, you can run any adventure. The universe is wide and vibrant with many planets that you can explore, as well as space stations where you can lose all your money through gambling. If you ever need a hand understanding the system, there are also helpful video tutorials online made by Dyer to help ease GMs and players into the game. Now that we have concluded our trip through some of Australia’s best tabletop roleplaying games I feel like I have done my part. Now your part is to seek these games out, spread the word, and go on adventures you can only dream of. Mitchell Wallace is a writer, professional gamemaster, and twitch director for Penny for a Tale. Mitchell playtests, runs, writes, and plays as many tabletop games as he can, and loves sharing them with the world via twitch, twitter, instagram, facebook, and pennyforatale.com Picture Reference: https://www.tinstargames.com/#/ We all want to level up our characters and smash the "big baddies", but quests and campaigns can become monotonous in the name of grinding for experience. Endless cookie-cutter dungeon crawls can suck the fun out of a great campaign and turn game night into more of an obligation. Check out these five ways to keep the magic in your campaign and help prevent the characters from turning into murder hobos! 1) Think Your Way Through A Puzzle Getting creative with puzzle encounters can break the cycle of beat the small baddies, beat the big baddie, get the treasure and experience points, rinse and repeat. Forcing your players to use critical thinking and their imaginations may be painful at first, but it can also bring new ideas to the campaign storyline. The puzzles don’t have to be on a high difficulty setting, sometimes setting up an easy or moderate puzzle can be just as fun to break the monotony. Try a small puzzle, like a mysterious room armed with coded locks that cannot be picked by your rogue. Or perhaps a larger puzzle of a strange cult that is controlling a village and needs to be dismantled via diplomacy rather than the sword. 2) Go Fetch! Fetch quests can seem trivial, but they’re also a fun way to push the story forward without a dungeon crawl. Have your players find a lost item that they must return. Then the reward can lead to a new epic quest, or an even more difficult fetch quest. The players might even decide to stay awhile and explore the new town or setting. Or the fetch might be an NPC (non-player character) or an enemy creature. Perhaps the princess has run away from her engagement and you must return her to her betrothed. Then there lies the choice of forcing her to marry, or allow her to escape. A new adventure awaits. 3) Introduce A New Threat Perhaps the main quest is ultimately defeating a particular big baddie and their lesser baddies along the way. However, that doesn’t mean a side quest isn’t in order. Create a new threat for your group to face. Maybe a town is being held hostage by a rogue warlock? Or perhaps a village is plagued by a rag tag army of bandits that assembled in the name of looting? Taking a detour from the main quest can be just what your campaign needs. 4) You Can’t Shake A Sword At The Plague An unusual route your campaign can take is dealing with a quarantined town. You can’t fight illness with weapons, or perhaps even magic. The villagers need saving all the same and riches may wait as your reward. A twist on the puzzle quest, figuring out the cause of an outbreak and finding a solution or a cure can put your group’s imaginations to the test. It can also allow your healers to shine as the key players for the quest. The cause of the disease could still be due to a baddie that needs to be slain, but the journey to that knowledge would be different from the typical dungeon crawl. 5) Make A New Friend Once a party is established, the dynamics of the group can become stuck in a rut, and gameplay can become quite predictable. A great way to shake things up is for the DM (Dungeon Master) to introduce a new NPC to the party. It could be temporary for a single quest, or could be a permanent fixture for the remainder of the campaign. Either way, it gives your party a new character to fight alongside and learn their quirks. Just be sure not to give your party a broken NPC either way – making them overpowered will make gameplay boring as it removes all the challenges, and making them weak and dumb will bog down your party and frustrate them. Meet somewhere in the middle with good advantages and weaknesses for the best gameplay. 6) Put The Game On Pause Sometimes the best way to rejuvenate the grand campaign is to put it on hold and have fun with a one-shot campaign. Pick a storyline that’s radically different than the quest you’ve been grinding on, and watch the spark return to your group as they battle their way through new monsters and challenges. A little fluff can go a long way to bring back the magic. It can even resemble the old dungeon crawl grind, but having a new storyline and objective can give your party the new angle they’ve been craving in their main campaign. While taking a new turn with your campaign can be fun, it's important to keep the balance of the overall goals of the campaign. Don’t just throw a crazy left turn into the mix, as that will only frustrate the party and confuse the campaign goals. Though if your group has a craving for plot twists, or straight up nonsense, perhaps they need a one-shot in a wonderland of sorts? Alice Liddell is an author, artist, and performer who loves bringing magic and fantasy to all aspects of her working and personal life. Whether it’s DnD with friends, or a round of Fable solo, Alice has always loved gaming of all kinds. You can find her work on her social media handles Facebook, or under littlalice06 on IG and Twitter. Image link: https://pxhere.com/en/photo/1021946 Once you have a world, you need to build a campaign, this will give you an idea on where to start.